Art-appreciating dolphins

Here's the dolphin's eye-view of our boat. As you and the dolphins can see, we adorned it with an enlarged line, taken from a painting of mine.

We hoped to make it a distinctive craft. The squiggle works in place of a name, just like the singer who once tried the same.

The curious thing is that whenever we're visited by dolphins while out sailing, they display what can only be an interest in the art. (I wish they had money, and could buy as well, but that's another story...)

Anyway, instead of the usual coming from behind parallel to the boat’s course, and surfing in between the hulls on the pressure of the combined waves from both bows, since the painting the dolphins streak in from the side, and at the last moment turn on their sides to have a good ol' dekko at the line.

The graphic is in dark red, so it could be they see an alluring and interesting splash of blood - they are top end predators after all. But I, being what I yiz, reckon they like the work. These are dolphins with an advanced art appreciation I say.

An artist is always seeking affirmation - even if from other species. The artistic visual world of the dolphins must be somewhat limited. Blue. Deep blue. Nothing but blue. And more blue. With occasional fish. Which must be eaten.

So perhaps they make their own art out of streams of bubbles. Or one could say they do aerial (and underwater) gymnastics, with the way they frolic. Perhaps they even have competitions, and contestants are scored up to ten, by grumpy oldie sport administrators holding up placards (or blowing the right number of bubbles.) Perhaps they even have controversies over rigging of scores, favoritism, and what 'artistic interpretation' really means. Just like we do at the Olympics. At least they seem to take synchronised swimming seriously – or at least build it into their daily workout regimes.

But does my anecdotal evidence stack up? Here's a special example. Off Tikitikiatonga Point (near Horuhoru/Gannet Rock) a wee while ago, three dolphins came past and took a look at the line. Swish, flip, splash, pffht! (blow) and again. They were distinctive, being big dad, medium-sized mum, and small baby, sticking close. They hung around for a minute or so, doing the looking at us from the sides thing, and then I imagine the littlie's attention span wavered, and they wandered off.

I invited them back anytime, by calling to them when they last surfaced. I hoped they heard. Sure enough, five minutes later, they returned, bringing about 20 more mates. We recognised the original three among them.

They all did the art appreciation thing again, as if showing their friends an interesting show at the human gallery. And then did a fine jumping display for us, which lasted twenty minutes or so. Was this reciprocation - a kind of art exchange? What they were doing was certainly not the usual humdrum business of hunting. This was something else, something recreational. And it appeared to involve us.

I wish we could have asked what was going on. Maybe the line on the boat was doing the talking. Some language experts say we'll soon be able to speak dolphin. But in the case of the visual language outlined above, I do believe we already do.

Holding up self

It’s that time of the year. Our thoughts turn to sculpture. My thoughts had me linking one special kind of sculpture, to the state of the world. I reckon it’s a strong metaphor. See if you can follow my drift.

Imagine you’re holding up a piece of rope with a seat hanging from it. Now imagine sitting in that seat. Nah – it’s not gonna work. But don’t you wish it would? Call me crazy, ‘cos I live with the hopeful belief that such things are possible.

It’s an enduring fantasy of mine, to float on a stage of my own levitation. Of my own creation. Of my own support. Of my own construction. Or at least of my own ‘faluting imagination. It’s kinda like a quarter-pie type of physics – plausible, impossible, magical, absurd, all at the same time. The logic should work: you hold it up, so then it can hold you up. So much for instinct. (Perhaps that’s why I’m not a millionaire – but’s that’s another story altogether).

Trouble is, in this real world of harsh reality, these things can’t happen. You can’t hold up your own hammock. It seems physics cares not for ridiculous reciprocity. There’s no free lunch where gravity lurks. Well maybe we can trick it (gravity) – or at least physical things (likes sticks and string). And in doing so delight ourselves with sculpture and symbolism.

It’s called tensegrity sculpture, and I can’t think of a more useful metaphor for our collective situation in heading into this uncertain year. We’re will simply have to hold ourselves up, by whatever magical means possible. Bring on the wizards! We need ‘em. Or we may have to become them ourselves.

Here’s the curious thing: although entirely possible, and quite simple really to get sorted, tensegrity has no deep and essential foundation story in our discovery of the physical world. After all the eons of human inventiveness – we had already come up with radio waves, photography, flight, you name it – when some artist figured out tensegrity. Around the 1960’s in fact.

It reminds me of that bumper sticker that posits the cheeky query, “What if the hippies were right?” It seems in this case, they were. Well, maybe it was the zeitgeist that did it, for there are a few claimants to the ‘invention’ of tensegrity sculpture. Whatever – I still think we can use the symbolism now. We’re floating precariously; we’re held in screaming tension. There’s so much that just doesn’t stack up in the world at the moment. Here’s hoping we don’t all fall through the cracks of our own making. Maybe we won’t.

To the facts: “Tensegrity,” we’re told by definition, “is a structural principle based on the use of isolated components in compression inside a net of continuous tension, in such a way that the compressed members (bars or struts) do not touch each other and the pre-stressed tensioned members (ropes, cables or tendons) delineate the system spatially.” Another definition reads better in Dutch: "De touwtjes houden het hele bouwsel bijeen en de houtjes uit elkaar." Which translates to, "A set of strings that keep the construction together and the sticks apart." (From an article by Chris Heunen and Dick van Leijenhorstand.)

The great flawed genius Buckminster Fuller coined the term tensegrity. But that was when he appropriated a student’s artwork, and even exhibited it himself under his (Fuller’s) name. It takes a lot to be a celeb.

Before that, the very simple 3-strut tensegrity prism was first created either by Lithuanian artist Karl Loganson around 1920, or by Ted Pope, another Buckminster Fuller student in the 1950s. But both Karl and Ted did not do much more to develop the idea.

The pivotal student was Kenneth Snelson. He used the term ‘floating compression,” and has since been more closely associated with the vision and its manifestation.

Almost all public tensegrity sculptures, and they are around the world, are by Snelson. Here’s the sad (and topical) thing: Snelson died just recently’ aged 89, of prostate cancer on the longest/shortest day of the year, 22 December 2016. An interesting element to Snelson’s career is this: he “emphatically rejected” (says the New York Times in his obituary) the description of himself as a ‘quasi-scientist.’ He said: “My sculptures serve only to stand up by themselves, and to reveal a particular form such as a tower or a cantilever or a geometrical order probably never seen before; all of this because of a desire to unveil, in whatever ways I can, the wondrous essence of elementary structure.”

So the analogy continues: without Snelson, we’re on our own now. But the wonderfulness of elementary structure persists. As does good art. Let’s keep it (ourselves) together.

* Afterword: by the way, Snelson was a generous man: you can have a book about him for free. Just download Art & Ideas from the web.

Art in the Pre- and Post-Covid World

In alphabetical order, some names you may recognise:

William Baziotes, Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, Diego Rivera, Mark Rothko, Joseph Stella.

Some you may not:

Berenice Abbott; Jozef Bakos; Fay Chong; May Dwight; Angna Enters; Alexander Finter; Marion Greenwood; Axel Horn; Aitaro Ishigaki; Sargent Claude Johnson; Georgina Klitgaard; Blanche Lazzell; Moissaye Marans; Louise Nevelson; Elizabeth Olds; Gregorio Prestopino; Misha Reznikoff; Mary Scheier; Dox Thrash; Edward Buk Ulreich; Stuyvesant Van Veen; Andrew Winter; Jean Xceron; Edgar Yeagar; Bernard Zakheim.*

What’s the connection? They were among the 10,000 visual artists supported in the USA during the Great Depression’s Federal Arts Project. Now it’s not every visual artist whose reputation grows to become a world-famous household name. (The first list is way shorter than the second) This hardly negates the validity of the work of all the others. And the work of Depression-era artist has been preserved for all to see. Their works became the property of the people, and were hung if public places.

Under the system, devised by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s wide-ranging, far-reaching Depression-era mitigation policies, artists of all stripes – see below – could find employment, and be paid, modestly yes, for their work. It was FDR’s New Deal at work. Economists are saying the Covid-19 pandemic will result in Great Depression-like downturns. Maybe now’s the time to see how good ol’ FDR dealt with things that time around.

The different Federal support projects for the arts were all under the aegis of the Work Progress Administration (WPA). Mostly the WPA employed millions of job-seekers (mostly unskilled men) to work on infrastructure projects for the public good, including the construction of public buildings and roads. But then, FDR’s "American Dream… was the promise not only of economic and social justice but also of cultural enrichment."

So the WPA started to included artists. This project was the first where US Federal money was used on culture. The Federal Art Project operated from August 29, 1935, until June 30, 1943. It was created as a relief measure to employ artists and artisans to create murals, paintings, sculpture, graphic art, posters, photography, theatre backdrops, crafts – you name it. An additional outfit, the art-research group worked on the Index of American Design, a mammoth and comprehensive study of American material culture. Artists were paid $23.60 a week; tax-supported institutions such as schools, hospitals and public buildings paid only for materials.

Then there was the Federal Music Project. This employed musicians, conductors and composers. In addition to performing thousands of concerts, offering music classes, organizing the Composers Forum Laboratory, hosting music festivals and creating 34 new orchestras (!), employees of the FMP researched American traditional music and folk songs. Those researchers did good work and produced studies on cowboy, Creole, and what was then known as ‘Negro music.’ A Dr. Nikolai Sokoloff was the director of the Federal Music Project. Trouble is, he was a classical music conductor. He was accused of highbrow bias. Charles Seeger (father of Pete) became assistant director of the project, spreading the good cash to many more varieties of music. Free, live performances of African American and Hispanic music were a hit. In many states there were efforts to document the music of ethnic minorities, spirituals, work songs and other folk musi.

The Federal Writers’ Project cost the nation approximately $27 million – one fifth of one percent of all WPA appropriations. Same deal: you got paid to do your work, even if it did get you a regular job. The Writers’ Project also gave jobs to unemployed librarians, clerks, researchers, editors, and historians. It kept 10,000 wordsmiths off the streets.

Finally, the (much cheaper – why? Dunno) Federal Theatre Project. It was allocated only one half of one per cent of the allocated budget from the WPA. But was still a commercial and critical success. But uh-oh, the project became contentious. The House Un-American Activities Committee (bad buggers, these) claimed the content of the FTP's productions were supporting racial integration between blacks and whites (yikes!); while also pushing a communist agenda (treasonous!). The silly committee cancelled funding for the project in June, 1939 But the Federal Theatre Project had employed 15,000 good folk, also paying them $23.86 a week. Seems like it was the standard WPA pay. More big numbers: The Theatre Project played to 30 million people in more than 200 theatres nationwide — renting, re-opening many that had been closed up — as well as parks, schools, churches, clubs, factories, hospitals and closed-off streets. Two thirds of its productions were presented for free to the audience. Cool! Maybe we can do that after lockdown.

The different Federal Projects supporting the arts wound up just before or during the Second World War. The War was good for business, and the USA economy looked up. Artists were again supposed to find their own work.

To today: which country supports artist (of all kinds) the most? No prizes for guessing, they are the Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. In Germany, the Artists’ Social Security Act has been operating for more than 30 years and provides health insurance, the old age pension and nursing care for self-employed artists. Canada, Australia, ourselves – indeed most modern western democracies – have government-funded arts grants schemes. These are all run on a contestable basis; which has its own pitfalls.

Just being paid to work, like those artists in FDR’s New Deal, seems like old history. But to go into that is a whole new investigation. Next time maybe.

*Google them. They are all interesting. And in these lockdown times, we all have plenty of time to indulge in diversions.

Among the Cinders

In New Zealand you can take off, carefree, and wander the country-side in an unhurried, unplanned fashion. You can escape your worries. You catch fish and shoot rabbits, and roast them on a bright, fragrant campfire, and filch apples and potatoes and turnips from orchards and farmers’ field for food. You meet beautiful, sharp, uninhibited women (if you’re an ardent young fella, like the hero). You have a harmless and funny old sage for company, and meet many more on your travels; and an arching sky of the brightest stars sings to you at night. There are mountains and trees and funky old cars. It rains occasionally, but not much, and this doesn’t infringe too much on your grand adventure. But you do have to change plans. You’re called on to be decisive. And you come out of this wiser, and somehow more in tune with the cosmic goodness that surrounds us. Happy ending.

It’s not exactly how the book runs, but this kinda paraphrases Maurice Shadbolt’s novel, Among the Cinders, and its enduring effect on a generation of German travelers to Aotearoa/New Zealand. And in this lies a tale of the power of myth-making, of the danger of getting lost in translation (twice), and the unfathomable, immeasurable – and sometimes unexpected – impact of art (in this case evocative fiction) on people far away. We’re creatures of the story, I always attest, and here’s one story that has captured and transported many. Though, like real life, it has its share of let-down.

Shadbolt was a great New Zealand novelist, to be sure, best known for the Lovelock Version, a rollicking family saga, and his three novels with a sardonic – nay quirky – take on the colonial conquest for these islands. These are his métier – Season of the Jew, Monday’s Warriors, and The House of Strife, can be called revisionist history, but mostly they are stylish and entertaining stories. Someone once said that history is a story, rich and tangled and funny and weird and not always true like true is a one-sided reality, and that these novels reflect that to an excellent degree. I agree. And so, possibly, would George Fairweather, the amusing (if confused) ‘fresh-off-the-boat’ narrator of these three tales.

The first novel published by Maurice Shadbolt (rest his soul), Among the Cinders charts the story of young Nick Flinders, a good Kiwi lad, who’s taken away to distract him from death by his granddad Hubert. Their trip through the backblocks, and meeting Sally, is the action and essence of the story – see very loose rendering, paragraph one, above.

But here’s where it gets interesting. The book, apparently, was far more successful in its German translation. And so inspired a large audience in that country with a romantic vision of this country. Which lead to the steady stream of German backpacker tourists coming to find themselves here. (You may find some this summer). Whether they’ve actually read the book, or simply absorbed the Cinders zeitgeist from diverse sources in the collective subconscious of their country, is a moot point.

And so it happened that German money, and a German director (no problem with that) came to make the feature film of Among the Cinders. Only it never got to theatres in NZ – it’s only had one TV showing here. Reviews are a little faint. One says the movie is closer to the translation of the book, than the original version. But the old guy gets a good mention. And the poster, and Nick and Sally, look suitably stirring and romantic.

Is this a case of the story – and the myth it created – being stronger than the technicolour package of pictures? If so, there may be a lesson in that – for all of us, backpackers, directors and indigenes alike. Of countries there, islands here, and places in the mind.

Dear Patty and Mildred - how Happy Birthday came to us

“A good morning to all, a good morning to all, good morning dear children…” If you were to sing these words, an instantly recognisable melody would emerge.

Chances are, you most likely substituted the words happy birthday for good morning, and the song rolled on just fine.

Truth is, the song started as a good morning ditty composed in 1893 by sisters Mildred and Patty Hill, in Kentucky in the USA. There was a third, youngest sister Jessica, who also plays a part in this story.

Happy Birthday to You is the most recognised song in English, with For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow coming in a far-away second. Happy Birthday works in translation in 18 other languages as well.

And though we all know the words to the song, I’ll bet you don’t know (I didn’t) who wrote it. Supposedly. But more of that later.

Patty Hill was the head teacher at a kindergarten in Louisville, and her sister Mildred played the piano and wrote her own songs. Patty espoused progressive ideas about early education. She thought it would be a nice idea to start the school day with a jaunty wee song to lift the spirits.

It caught on, and before long it was being sung around the state. The substitution of ‘happy birthday’ for ‘good morning’ must have come about quite naturally. No one knows exactly when and how, but I’d imagine that with a child in the class having a birthday on that day, hey presto! – here’s a song ready-made to fit.

The words and melody of Happy Birthday first appeared in print in 1912, but with no song writing credits attributed, but no worries, for a while people sang along happily anyway.

Happy Birthday appeared in the new talking (singing) movies, and on radio. In 1931 it featured in a Broadway musical The Band Wagon. Then Western Union used in their first singing telegram. After the song was heard again from a Broadway stage in 1934, Jessica, the youngest Hill sister, thought she had secured the copyright of Happy Birthday in 1934, on the strength of its identical melody to Good Morning To All.

Then in 1935, things around the simple song got complicated. Some people disputed whether Patty and Mildred had actually written the song.

No written proof could be found attesting to this. An outfit named The Summy Company filed for copyright on Happy Birthday, claiming that It had been written jointly by one Preston Ware Orem, and a Mrs R R Forman.

Orem was a classical music composer associated with the Indianist movement, which attempted to tie together the musical ideas of native Americans, with those of the Western tradition. Good luck to them.

Of Mrs Forman, I can find no more detail. Anyway, Summy started charging royalties on the public use of the song – not around birthday cakes in homes mind – that would be too difficult – but in films, on stage, at public events. It made a bucket load of money.

Then in 1988, Warner Chapple Music bought Summy, the company, for US$25 million. Their big asset was Happy Birthday, estimated value US$5 million. Warner thought they’d be sweet owning this copyright until 2030.

Things didn’t work out this way. In 2013, a filmmaker named Jennifer Nelson got grumpy. She was making a documentary about the song, but Warner would not let her have a clip of the song in the film without paying royalties.

She filed a lawsuit. Finally, in 2015 a judge in the USA ruled that Happy Birthday to You is not under copyright. So royalties will no longer have to be paid to Warner Music for its use.

In the European Union, copyright for Happy Birthday expired just recently, on 1 January 2017. And you’ll be pleased to know that Mildred and Patty (but not Jessica) had already been inducted to the Songwriter’s Hall of fame, in 1996.

So next time you sing the song -somebody’s birthday must be coming up soon - you know all is cool. Happy Birthday is now in the public domain. Kinda like it always was. Phew.

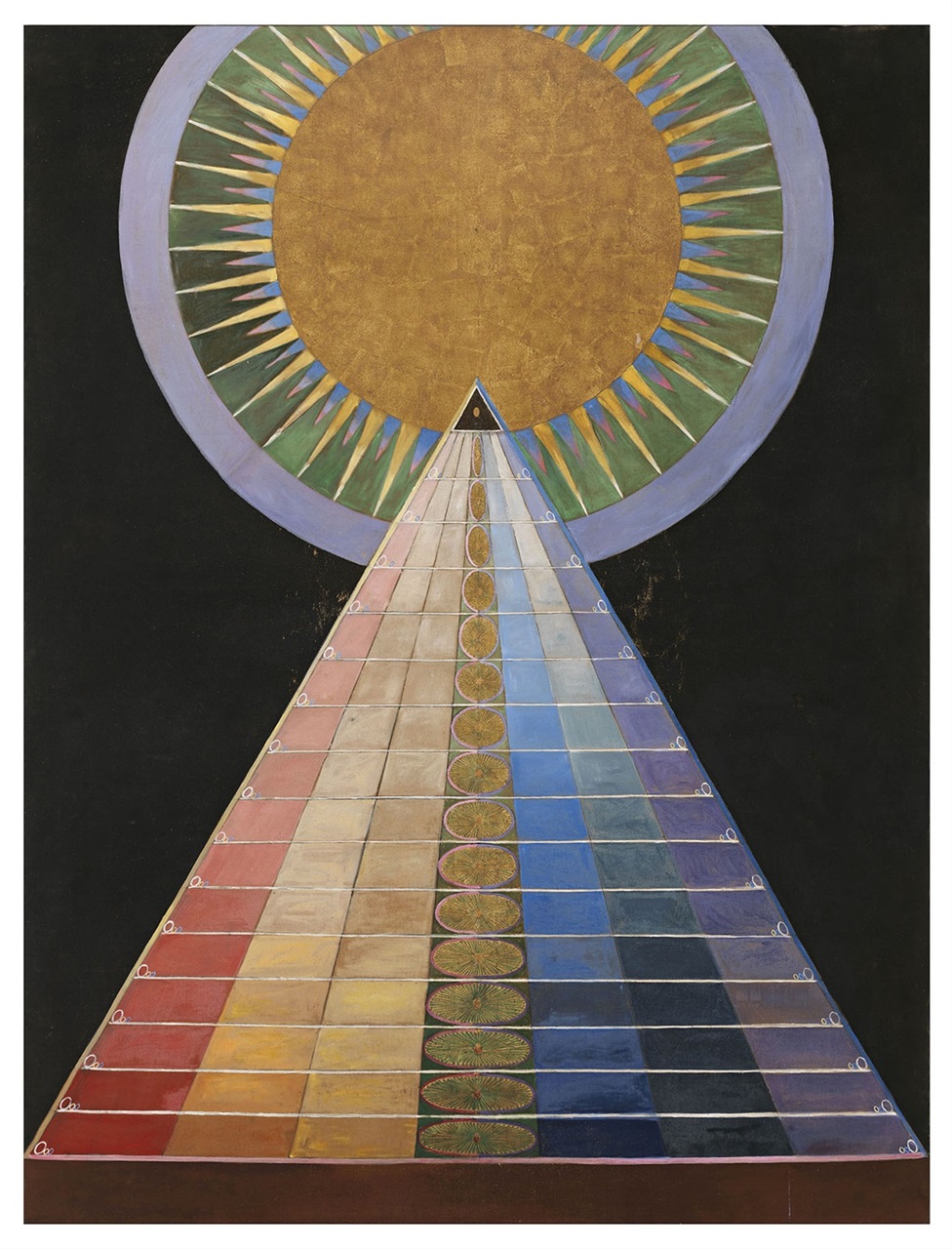

Disrupting the standard narrative - the art of Hilma af Klint

The standard narrative of the history of abstract art has it that the Russians Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, and the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian were the trailblazers of abstract art, producing purely non-figurative works in the early years of the twentieth century.

The story goes on in a linear fashion through other figures like Robert Delaunay and Henri Matisse towards the great abstract expressionists of the USA in the 1940s – Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko et al.

Now it seems the story needs re-writing. The first abstract artist, (in the Modernist Western canon at least) it appears, was a Swedish woman named Hilma af Klint, whose non-representational paintings predate those of any of the known protagonists.

Hilma af Klint belonged to a group called ‘The Five’, a circle of women who shared her belief in the importance of trying to make contact with the so-called ‘High Masters’—often by way of séances. Her paintings of these experiences became a visual representation of complex spiritual ideas.

But because they worked in relative isolation, away from the art capitals of Europe, af Klint has been overlooked until now.

Her art career began conventionally enough: she studied at the Academy of Fine Arts of Stockholm, known as the ‘Konstakademien’, where she learned portraiture and landscape painting. She was admitted at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts at the age of twenty. In the years through 1882–1887 she studied mainly drawing, and portrait- and landscape painting. She graduated with honours, and was allocated a scholarship in the form of a studio in a building owned by The Academy of Fine Arts.

Throughout her career, her more conventional work, mostly landscapes, provided her with income. Her abstract work was a hidden secret. Her younger sister Hermina died in 1880, and Hilma at this stage embarked on something of a spiritual quest. She and ‘The Five’ became interested in the occult, and engaged in much discussion of the spiritual self, and organised séances.

As early as 1896, af Klint experimented with automatic drawing, something the Surrealists picked up on a generation later. She believed some force was guiding her hand in producing a purely abstract visual language.

Her first purely abstract paintings were done in 1906. This was a series dedicated to a mysterious ‘Temple’, about which she had no rational explanation. Klint claimed that in a séance a spirit known as Amaliel addressed her directly, asking her to create the paintings that would line the proposed temple’s walls. The paintings she created were monumental. All this occurred without any contacts with the contemporary modern movements.

She wrote: “The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.”

The works were of value to her, and she retained them all her life, and in her will bequeathed them to her nephew. She stipulated they should remain secret for 20 years after her death. When they were revealed in 1960, the cache of 1200 works re-wrote art history – but slowly.

Even now, she is only a peripheral figure in the story of modern art. I’ve yet to find a book on the origins of abstract art that mentions her. The collection was offered in 1970 to the modern art museum in Stockholm, which initially declined the gift. It was only an exhibition of af Klint’s work in Los Angeles in the USA in 1986, that gave her something of an international prominence.

What are we to make of Hilma af Klint’s story? Just that conventional narratives of history may overlook things, and that for those who look deeper, history can be, should be, re-written. Hilma af Klint deserves a place in the history of modern art. She deserves to be a name we know.

Falling off the radar - the one-way art of Bas Jan Ader

There are plenty of stories of hopeful artists who have not yet made it, doing what they have to do.

Bloke I know, draws well in his own particular style, and a film-maker too – he’s now driving a garbage truck. I say that would give him plenty of good material. He to despondent to take up my suggestion.

One such half-forgotten character was Bas Jan Ader, an American conceptual artist of Dutch birth, whose mysterious disappearance perhaps has led to a greater recognition of himself than he would have if he had simply kept trying, below the breakthrough line.

The work for which Bas Jan is now known for is the artistic investigation of gravity; and his use of gravity as his actual medium. His individual works took the form of mini, truncated events. So he would film himself edging out along the overhanging branch of a tree until it snapped (or his grip gave out), and he plunged into the river below.

Or he would balance a chair across the top of a steeply pitched roof, sit there while edging bit by bit to one side, and eventually tumbling down.

Or he would ride his bicycle off the edge of the wharf into the canal. He might stand by the side of the road, leaning ever further to one side, to the point where he fell down.

I’m not sure if he ever injured himself in these performances – he often had the soft landing of water beneath him. But the fall from the roof of the house was real, and onto the unyielding earth.

With a friend, he produced a satirical art magazine called Landslide, which would feature interviews with imaginary artists, and suggest artistic shams such as ‘expanding sculpture’ (seeds in an envelope). While the magazine spoofed conceptual art, it has become to be seen as a conceptual art exercise in itself.

There’s no money in conceptual art (or at least it is notoriously difficult to monetise), so Bas Jan supported himself in California by teaching at art school.

He also did works that explored sorrow. A work entitled I’m Too Sad To Tell You has him crying on video. Perhaps the fact that his father was murdered by the Nazis in the Netherlands during the Second World War has something to do with that.

Bas Jan’s great work was to be a triptych, In Search of the Miraculous. The first part is a film of him wandering the streets of Los Angeles at night, shining a torch into darkened alleyways.

The middle part of the triptych was to be a sailboat journey across the Atlantic, west to east in the smallest possible boat, linking his two worlds.

And the last part was to be another night-time, torchlight perambulation of Groningen in the Netherlands. The triptych was to be his final work.

The first part went OK. And then, in 1975, he left Cape Cod in a 13-foot sailboat, to cross the Atlantic. He never made it. The boat was found, abandoned and only half afloat by Spanish fishermen, 100 nautical miles southwest of Ireland.

It appeared he had been washed overboard, as an anchor for his lifeline had been ripped out. Small sailboats had crossed the Atlantic, and Bas Jan was an experienced sailor, having crossed oceans before.

But his mother had had a premonition of his death. In a documentary film of Bas Jan’s life by Dutch film-maker Rene Daalder, an old sea dog was found who said he understood Bas Jan’s imperative for the sailboat trip. He was going to find the place where he could let go, like losing sight of the land, Just like the letting go in his gravity works.

Some say the sailboat trip was foolhardy, and in itself a vain attempt to approach the miraculous. He needed luck to complete it. As surely as gravity, his luck ran out.

One way for a little-known artist to be remembered, is to be martyred for his cause. Perhaps that’s what Bas Jan Ader was indirectly aiming at. But now he is remembered for making it halfway through a perhaps foolishly ambitious conceptual art triptych.

We gather fame in mysterious ways, artists included, and Bas Jan Ader’s story is a case in point.