Writing and art by Alex Stone

Came to talk

How the sharpest lies go soggy. How the cruelest deceit becomes ordinary misery. It was deceit that found me, unwitting, on this journey. It was a lie that led me here.

But there is reason for all this, though it may be the reason of unreasonable men.

This is my story:

Long silences. This voyage is built on long silences, it seems. Between me and my companion. Between us and the chief of this ship, this growling pale red man Willem deVlamingh. Between us and his strange company of men. Between all of us, and the ragged empty soggy sky.

Long silences. All except between this moving world of wood and cloth and the sea it lives upon. It speaks, this giant ungainly flightless bird they call Geelvink, all the time, as if complaining. The wood of trees was made to stand in the earth, to burn in fire for the warmth of men, us men-of-men, khoikhoin, not to ride on a world of water. That is the stuff of wrath, of floods.

deVlamingh, he showed us his instructions, once he had taken us, scribed in the white man’s hand on the thinnest piece of calf skin: there are no pictures, just malevolent lines, curled and knotted, miniature snakes that have lost their way.

deVlamingh, he tells us the meaning of these stillborn serpents. The message lies in the way they align, he says, appearing frustrated at our angry uncomprehending stares. The message, he says, instructs him from a chief of his land, far away, to take with him “Two blacks from the Cape”.

Blacks? Black is beyond the colour of night; black is the void, from whence Kaggen brought all the creatures to form our world.

We? Black? We kwekwa are the colour of life, of the earth, of a lion, of eland, of honey. We are the colour of all that is strong and worthy in this world. It rankles that they should see us black. But they do. They do not see much accurately, these ignorant men.

deVlamigh, he has a book, a great book of this voyage. He marks it every night, hunched over, with a black stick, and scribbles of furious concentration. He appears to be in pain when he does this. His stick gives birth to more thin black snakes.

He shows me the book. He says they speak, these marks he makes, in a language we can choose to hear, or not.

For this story, which I am giving to you now, wherever you might be, in whatever part of my future you are, whether I am there or not, I trust not to this strange language. I commit this instead to my thinking strings, so that I might altogether speak with you, in our own way, in the manner of the khoikhoin, men-of-men.

deVlamingh, he deciphers his book for me — but who am I to trust he speaks with verity?

The book is a story of our days, he says; of the stuff we have lived, the stuff we already know.

Why record it, I ask, if it is not a real story?

He shows me what he calls a date. This deVlamingh, he says it is a record of the year we are in; a number. It says 1696.

But why should we count the seasons, I ask him? We, the men-of-men, the people of this dry earth, who have been here since the beginning? Since Kaggen gave us light, and life, and brought us out from the black.

Why give the years a number? The only number that matters is that of a man’s cattle, his fat-tail sheep, a man’s children, a man’s wives. Why give years a number? It is futile.

It is futile, I say. deVlamingh cannot answer; and only glowers, and slams the big book shut with a finality.

There are many questions. Take with him? Where too? But if I have no answers, of course I had no choice.

My father had promised me, a complicated investment in future livestock trading privilege, in which I had no say, and only this limited understanding. My father trades beasts with the Dutch, wants to continue trading with the Dutch. So he lends his youngest son, when asked. And a second, a pathetic refugee from way beyond the Gariep, a Damroqua who cannot find his way home.

So we must go with this man deVlamingh, and travel to another world.

And what must I do when I am there?

deVlamingh, he tells me: My companion and I have come to talk.

With whom? I ask.

With the black people of a strange land.

And how should I talk with them?

deVlamingh, he answers thus. You are black too. You should be able to speak their language. These are my instructions from Holland.

Such is the limited reason of unreasonable men, is my thought to this. I tie it to my thinking strings, as I take my leave of my father.

*

I don’t like my companion much. How we were thrown together in this way is a long story. Another story. To be told around a campfire sometime, under the brittle stars of a cold Tankwa Karoo night. To children, my children, who would listen.

We have learned the language of the grumpy red men, of course. They know nothing of ours, beyond our names — and those they pronounce hideously.

There are two women for the pleasure of men on this ship. One for all the crew, one for deVlamingh and his advisor. This advisor, it seems, is a powerful man, an emissary of deVlamingh’s chiefs. He has no interest in women.

deVlamingh, he shares the woman with me. (He is, in some respects, a reasonable man.)

The woman, she and I practise a universal language. We speak it well. After all, I have, per instructions, come on this long voyage to talk. I must not forget.

This voyage is endless. It seems this ship must push the entire ocean apart to move at all. This is a task that would be daunting even for the greatest of beasts, elephant or buffalo. The ship obviously, strains to accomplish this, and speaks in endless groans.

Is it alive, this beast you call Geelvink? I ask the headman. And deVlamingh, he laughs. As best as these men, who are so unused to it, can laugh.

My companion has taken to sleeping with the sheep in the kraal in the middle space of the ship. One night I found him asleep, asleep as the tortoise in the winter, with his hands cupped (for warmth, I hope) around the balls of the biggest ram. Should I worry for him?

As for me, I share the great cabin with this man deVlamingh, his advisor, and the woman.

*

We find a shore. The ocean ends, after all. As only those who have travelled through wastes of this nature, of this extent, can understand the profundity of an edge, an end, an arrival such as this.

The men stop the ship behind a low, flat island. They drop a great hook over the side, for once to hold this shambling Geelvink fast to the earth below. We lie still between the island and the great land.

An expectant space ensues; like the white space between the scribbles of deVlamingh in his great scribble book.

deVlamingh, he tells me we have come to search for men of his rude race, who may have lost their ship and themselves, on this strange shore fifty years before. There are other people here too, deVlamingh he tells me, the black people, who I must speak to. We will look for them. Perhaps they will know of the lost ship and its lost people.

They are ghosts you are hunting, I say. This is not manly work.

The island reveals a worn piece of wood, maybe from a ship. But no men.

We must go to the big land, deVlamingh he tells me. There is a river there to explore.

But what of the elephant, I ask? The buffalo? The eland? We must first appease them, before we visit uninvited.

This man deVlamingh, he grunts.

At the river, deVlamingh, he orders his men to fell some birds, that we may take them as food. Their sticks of great sound speak, and as many fowls as are in my family lie dead. They are large and black and sinuous and lovely.

We feast on them in the ship that night, boiled with much pepper. deVlamingh, he tells me, he will name the river, Zwaanien, after the birds we saw, shot, and ate here. Fair enough: it’s your imagination I say.

We do not see the men we have come to see; only their fires, their footprints. deVlamingh, he thinks these people are cowards. I think they must be cautious, as I would be. Especially after the display where the birds were felled.

On a second trip to the land, we see them. They have the look of Strandlopers.

Fine men, not a scrap of fat on them. Their women likewise, though their buttocks are shamefully scrawny. But they do look strong, and fit, and can obviously walk, and dig. Which is good.

The men, when at ease, rest a foot on one knee while standing. Each man always holds a handful of spears. In each group, one person holds a burning stick.

They treat fire as a child does a pet kid. Do they hold it for comfort? For affirmation? Is the fire a possession? They appear to have little else. I see no herds. What do these men eat? What is their wealth?

Their colour is that of the darkest mud. But they are not black. No man can be black, for that is the colour of the void; of the time before. That is why some birds may be black, for they may escape the dark with their wings. They have black birds here, just like our crows. They attend us, moaning in a dire manner.

We meet these people three times, each un-auspicious, each disturbing, each perplexing. Anger shimmers in the air. My companion and I, we know this well. Is this what we have come to translate? Perhaps those who instructed deVlamingh know this; this language of resentment, and shame and impotence we know so well. And they are entirely ignorant of.

1st meeting

This is not a meeting; a fleeting glimpse, say of a rhebok, that leaps up in front of you.

There are three young men. But somehow, like the rhebok, I know they will run some way, two hands-paces of the land, then judging themselves to be out of danger-distance, will stop and look at this strangeness again.

And their gestures are unmistakable. They shriek. They wave their spears at us. With their burning sticks, they fire the scrub in front of them. Through the smoke, they move their arms repeatedly toward us, against us.

Go away, they say. They are clearly terrified. This I understand, though I do not understand their language.

2nd meeting

They come to us. There are a great group of men, from the youngest to the oldest. Why are the young ones not herding cattle? I suspect they have no cattle. Where is their wealth then?

They carry long spears, taller than them, and shorter, broader sticks. Do these men know not of the bow? How can they pierce the birds? Behind them, crouching, hidden, are the women.

I feel a hand in my back, a trembling hand. deVlamingh presses us forward. And so we, my companion and I, stumble a few paces toward them.

They stand their ground, but I see them stiffening, their eyes widen briefly, then are squinted back to slits again. I smell their fear. Or is it mine?

We stand as intermediaries under this burning sun, on this place of loose sand. It suddenly strikes me as apposite that our colour is halfway between that of their skin, and that of the men of deVlamingh. I know this; when I paint with the black blood of eland liver, and the white of its milk, so do colours mix and become something new and in-between. But painting is not what we are here to do. Besides, there are no eland to paint.

How long I stand thinking like this, I cannot tell. When I return , we are all standing in the same place, though it seems the men of deVlamingh are further away, the tall dark men closer. We are still a speck between them.

deVlamingh makes one of his throat noises. He calls my name. We have, I remember, come to talk. These are his instructions.

I greet the tall dark men in my language. They say nothing in return, and stare at us with a grim demeanor. I greet them in deVlamingh’s rough speech. They say nothing in return. I try all the languages I know. Nothing.

I take another step forward. They startle, and raise their spears, left arms raised, crooked, in front of their faces. One man turns side on, and looses his spear at a tree. He uses the curious shorter stick, which I can only call an elbow stick, to push the spear faster. His spear flies straight and fast, and in an instant lies quivering, deep in the chest of a tree. We get the message.

This man moves forward, cautiously, to me, a woman close behind him. He has scars on his chest, as the amaXhosa do scar their faces for pride, for family, for the ancestors.

He steps aside, slowly. The woman touches me. I respond, as a man must. We are, after all, men-of-men, and walk always half ready. Unlike these tall thin men with their strange hard eyes. Their third leg does point straight down, at the sandy ground.

The woman has no buttocks to speak of. Do these people value nothing?

And so is our second meeting. We return to the ship.

By signs, I had been able to say “We shall meet again tomorrow.”

3rd meeting

And so they are here, in the same place, in the same lines.

And suddenly, the men stand aside. It is as if they vanish.

A row of women replaces them. This is great magic. Then — curious thing — with a wide, slow gesture, they lift their baleful eyes to ours, extend their bony fingers, stretched taught out towards us; they hold this stance for a moment, then the hands move again, and slowly, surely, they take hold of their own breasts, with arms crossed. And proceed to squirt streams of milk as us.

We stand dumbfounded. This is beyond our horizon of possible comprehension. My thinking strings cannot stretch to this, even beyond the skyline, and into anchor points in the night of yesterday, tomorrow, or the time before.

We are out of range. The milk falls.

Though deVlamingh is anointed by a wizened woman who runs up to him, fixes him with a direct stare, and spatters the front of his waistcoat. He stands, aghast, still.

On the way back to the ship, my companion disappears.

deVlamingh, he comes to me, confused, anxious and alone later that night. I am squatting, as usual, arms around my knees by the small fire at the front of the ship. Not talking.

Our fire sits in a small clay pad, the only bit of earth to come with us from home. The stars above are the same though. We spend much time here, in this corner of the ship. We never go into the rank darkness below. At least we have the sky here. Why do I talk as if my companion is still with us?

My companion had long gone silent. Perhaps he lost the faculty of speech, the will to speech, in his state of shock. His still made music — an under-pitched keening wail, words indistinguishable, interspersed with sobs. Perhaps he will now share it with those people.

His singing matched the blue grey world that surrounded us, and had the same sense of forlorn-ness displayed by the great white birds of these mountains of undrinkable water. Birds that flew without moving their wings. Were they the vultures of this desert?

deVlamingh approaches cautiously, keeping low to keep his face in the light. He’s almost crawling, hand brushing the floor occasionally, to keep his balance. His is a sideways gait; he’s a brown hyena. He seeks explanation. I have none.

*

The ship lies in the shelter of the low island. It is cuffed by a great storm — as a lioness would to discipline a cub. Only here, the result is fear. The ship keens like an entire clan of mourning women. The wind tears at their hair. The women reply, louder.

The men of the ship heave extra hooks into the water. Will this appease the gods? No, deVlamingh roars at me, it is to claw the ground beneath, to stop the ship sliding, being crushed on the rocks of the shore. Such is the paradoxical nature of this damp and unnatural world.

In the heart of this great storm, I commit these words to my thinking strings, so that you may receive them. And may recite them in wonder around a fire under the stars of the far Karoo.

This deVlamingh, he commits his words to scratching. The woman lies, uncomfortably awake, staring at the roof, and playing with her hair. The advisor is with the men. My companion is lost. I am with my thoughts.

This story must end, like all good stories, with much left to run. deVlamingh, he tells me we must now go to another land, where there are true riches. Not a barren land and dark people with no cattle. We will leave our ghosts.

These words are now with my thinking strings. May that you will find them, retrieve them, and speak them again.

May that they be heard. Will this storm never end?

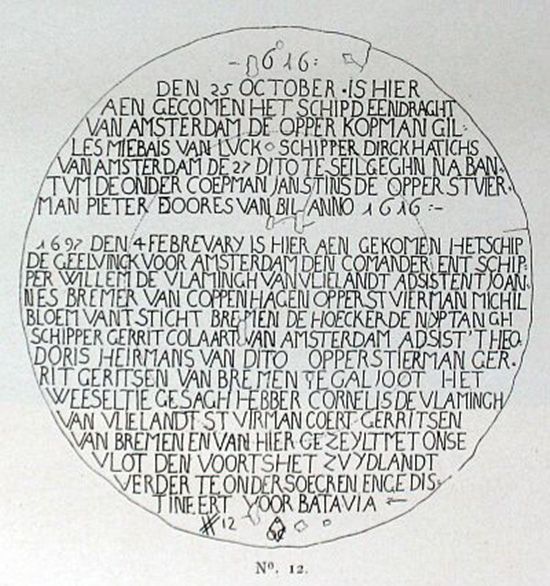

It is true that in 1696 Willem de Vlamingh did receive orders from the Dutch East India Company to pick up two interpreters at the Cape on his way to searching for shipwreck survivors on the West Coast of Australia.