Writing and art by Alex Stone

He Whakaputanga or We were a country when?

He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nū Tīreni, otherwise (but not really better-) known as The Declaration of Independence [by The United Tribes] of New Zealand, was signed by 34 rangatira in Northland in October 1835, and by a further 18 chiefs up until July 1839. The first date was four and a half years before the Te Titiri o Waitangi, the Treaty of Waitangi was ushered in.

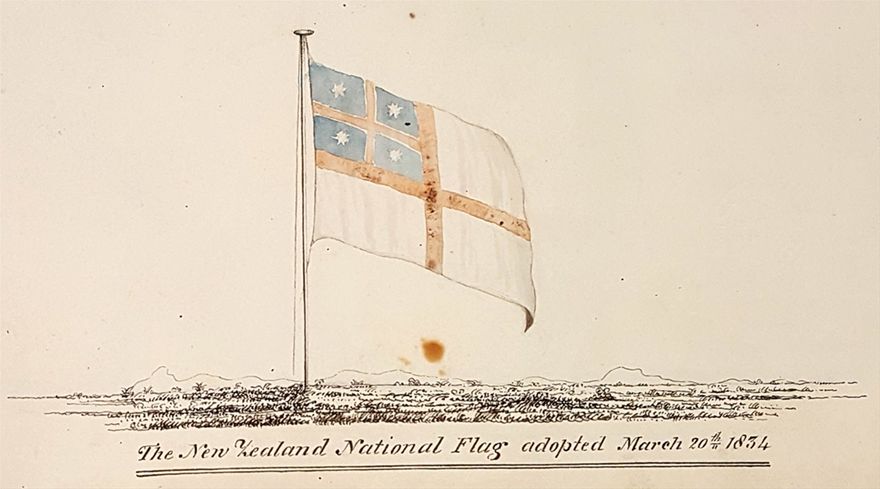

This all came about when, in 1830, a Hokianga-built trading ship Sir George Murray was impounded in Sydney, Australia, for sailing without a national flag, which contravened British navigational laws. The ship and its cargo could have been seized by customs officials; and was in fact briefly impounded. This was insulting to the mana of two Ngāpuhi aboard, Patuone and Te Taonui. At the time, New Zealand was not yet a colony of Britain. The simple solution was to create a flag, representing a new country. So this was done, by rangatira at a great hui at Waitangi in March 1834. The flag was named Te Kara. It’s the one we still see today.

It must be noted here that many ships that plied the waters between New Zealand and the East coast of Australia were Māori-owned. Indeed, the early days of the Australian gold rush were fuelled by spuds exported to that country, from Māori farmers and aboard Māori ships.

The signing of this Declaration of Independence was profoundly significant, because as historian Vincent O’Malley writes, “Even in the 1830s, Māori still continued to frame their thoughts and actions mainly in terms of their own immediate hapū.” So it’s clear to see why He Whakaputanga was “such a potentially far-reaching and radical measure.”

Another impetus for the Declaration of Independence was the arrival in 1835 in the Hokianga of one Baron Charles Philippe Hippolyte De Thierry, a megalomaniac nutter who had already declared himself ‘King of Nuku Hiva’ in the Marquesas en route. Northern Maori were wary of more interactions with ‘The Tribe of Marian’ – a reference to the visit in 1772 of French ships under the command of Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, where perhaps as many as 300 Māori were killed.

Now here’s the very interesting thing: Britain recognised this Declaration of Independence of New Zealand in 1836. France followed suit, reckoning that since the British had, so must they. And further afield, in the halls of power of another great and growing country, the USA Senate Committee on Foreign Relations noted that the North Island had been, ‘under the dominion of the native tribes, and these were to a great extent confederated. This confederation was entered into October 28, 1835, by a convention of chieftains who declared their independence under the name of the United Tribes of New Zealand.’ The flag would now be accepted on ships around the world, pretty much.

There is a cynical view that a country cannot be called a country until it has ‘settled parliamentary systems’ – but, hey, even if that applied today, that would probably disqualify a bunch of contemporary countries from Albania to Zimbabwe. But then, in the late 1830s you could have answered that He Whakaputanga, and the subsequent sessions of Te Whakaminenga – a congress of chiefs that met regularly – counted exactly as such. And yes, there are complications to this story, including the fact that He Whakaputanga was signed only by Te Ika a Māui North Island rangatira.

Some say the British resident at Waitangi, James Busby saw He Whakaputanga as “the most effectual mode of making the Country a dependency of the British Empire in everything but the name.” But he was wrong in that assumption – just as the British were, later, with the Te Titiri o Waitangi, their Treaty of Waitangi. That they tried to get all the signatories of He Whakaputanga to front up to sign again, is telling. As is the fact that they couldn’t. It’s fair enough, I reckon, to accept that people making a ‘declaration of independence’ are doing so on their own terms.

He Whakaputanga still exists; a fragile document of two cream-coloured paper pages. That is has been half-(conveniently)-forgotten, threatened by fire, and nibbled by rats also says something about our conventional history. In 1836, sixty printed copies of the declkaration were produced by William Colenso on a missionary society press in Pahia, and distributed far and wide. A year later, a hundred extra copies were printed. Yes, all in te reo Māori – so nothing can be said to be lost in translation.

All of which could lead us to something more to think about in our history. And perhaps, to consider that this is really the flag of New Zealand.