Writing and art by Alex Stone

Vernacular architecture - Motels

The classic seventies roadside motel: an often-overlooked contribution to New Zealand architecture. This is our concern right here – even though ‘architecture’, in this case, may rightly be considered with very definite inverted commas.

The opening up of the domestic tourism market in the 60's & 70's (a result of better roads, growing availability of cars, and more money for the average Kiwi family) made for a building boom in motels, and our current situation of a nationwide exhibition of the functional roadside hospitality architecture of this era.

So let’s begin with acknowledging this 'living museum' (for want of a better term), and go on to investigate the nature of a motel unit as a temporary living/sleeping space, its place in the current travel market, its image, and how little the basic concept has changed over forty years. All this inspired by a memorable motel room in Dargaville, where my wife and I counted eleven entirely different floral patterns in one small space!

Trouble is, the architecture establishment seems to hold no candle for the ordinary motel. Agreed, lot of them are pretty damn ordinary, but there they are – very visible, iconic features of our landscape that simply won’t go away. And if part of our future lies in an ever-expanding tourism sector, then they’re bound to proliferate further. We simply can’t ignore them.

In the light of the affectionate, and very pivotal place reserved in our self-made mythology for the simple, unpretentious, functional building in the form of the woolshed, the little country church, the simple seaside bach, this is deeply ironic. And since bach ownership has been declining, it’s probably true to say that for most of us, the majority of holiday nights we spend, have spent, will spend in the future, will be in motel units.

But take a look at writing about New Zealand architecture. Bugger all mention of motels. Open The Elegant Shed, by David Mitchell and Gillian Chaplin, a book largely dedicated to the vernacular in New Zealand architecture since 1945, and there’s no mention of a motel anywhere. Baches, corner dairies, small denomination churches, even your basic school gymnasium – but no motels. Mitchell was a wee bit nonplussed when I asked him the “but what about motels?” question. For him they just didn’t register.

So I turned to Looking for the Local – Architecture and the New Zealand Modern, by Justine Clark and Paul Walker. There I found a tyre factory, a kindy, a cement store, the Matamata rugby club grandstand. State houses. Council flats. A vehicle testing station. No motels. No mention. Not one.

Michael Fowler’s Buildings of New Zealanders has two chapters on design for hospitality, entitled ‘Last Orders’ and ‘Travellers’ Rest’. In 25 pages, one is given over to motels. But the tone is impolite. Very.

Listen to these excerpts from the photo captions: “Fenton Street [in Rotorua] has long been the favourite location of motels and hotels. The visual impact of the competing signs, so many of them tasteless beyond belief is reminiscent of the worst of the Las Vegas strip.”

Or, “Aside the highways of New Zealand, luring us from our cars and caravans , are the innumerable motels, offering us a bed, a shower, a stove to heat the can of baked beans; - anonymity and rest....Basic. Not much to elevate the soul, but sufficient to revive the body.”

This would seem illogical: if you already have your room on wheels, why would you need motel accommodation too? But recent research has revealed that one in four campervan holiday nights are spent in motels – so this may have happened in the caravan era also.

When did the word motel make the dictionary? Here’s the story: it’s a contraction of the two words motor and hotel, and first appeared in an American hospitality trade journal Hotel Monthly, in 1925. In New Zealand, the first motels appeared a few decades later. And in the nature of words since words began, ‘motel’ is busy morphing into ‘motor lodge’. A shift in the interests of style, not always substance. More on that later.

This leads to an identity issue for motels. For they are, in essence, not simply hotels adapted to motorists. Tradition says that a hotel is, has always been, a great, visible hub for hospitality, in the middle of the town, in the middle of everything. And so a hotel is built around a centralised greeting-meeting-eating space. A space which has still more uses – entertainment, a backdrop for civic events, a stage for the display of status. Which has reached its apotheosis in the grand public atriums of contemporary hotels. Which explains the varied lounges, eateries, bars and music nooks in the atrium. Which also explains why there are always the fanciest cars parked right outside the glass front door (not every car, as in the case of the motel). Why those front doors are so often of the revolving type. And why the atrium rises up through the interior storeys of the building, so a guest can always look down into, and connect with, the heartbeat of this binding space.

The real nature of the motel was put right to me in a conversation with Garry Tonks, of the University of Auckland’s school of architecture, who has designed a few motels himself. The essential form of the motel, he says, is that of a stable. Which figures. And which accounts for its generally unprepossessing aspect.

Look at one, and you may agree. With its long, low, generally one-sided aspect, and the separated stalls for the steeds (the cars), the motel is really a modern stable. It’s as if the grand hotel has decayed, been pulled down, swept aside by the construction of the road, or otherwise melted away, and all that’s left is the outbuilding. We’re there to sleep with the vehicle (perhaps like the horse grooms of old), and then move on. And this temporary sojourn is a shared experience, with almost no variation, from others in the same situation. Find shelter. Park the vehicle. Feed yourself. Move on. That’s what a motel provides. Nothing more.

Which is probably why motels are so often important, though inanimate, actors in road movies.

There’s a trend for new motels to be called ‘motor lodges.’ But sceptics say this is just trying on a grand title to be able to charge more. By rights, a real motor lodge should have a proper restaurant, and more privacy between units, than the regular motel.

John Sandford of Jasons TravelMedia, the company that produces the ubiquitous motel guide books, obviously knows the industry well. He laments the lack of design sensibility displayed by the majority of our motels. So many of them were built from replicated plans, he surmises, borrowed from someone down the road, or at best, from basic draftsman’s drawings.

“This is a real shame,” he says. “We must understand, as a nation, that good design makes a crucial difference.” In the case of building a motel, Sandford reckons a 10% investment in decent architecture and landscape planning in the initial building budget, will result in an ongoing 20-30% boost in income. Here’s another reason to invest in good design: repeat business, surprisingly, amounts to about half of a motel’s turnover, and this is not as fickle as the trade from passing traffic. At the Motel Association conference in July, Sandford heard the story of a motel that was doing very well, having raised that repeat business figure to 70%, after a substantial architectural and landscaping makeover.

When promoting motels, Jasons have used the oh-so-corny line (Sandford readily admits it) “your home away from home.” But as he’s keen to assert, it’s true. “Consider that the motel operator always lives on the premises; the reception desk often appears as a corner of his living area; and what could be more homely than the little ritual of handing you your small jug of milk for your cuppa?” So in effect, you as stay-over guest, are inhabiting the motelier’s own backyard.

This casual intimacy, Sandford says, should give moteliers a great advantage in attracting guests – especially those from overseas. You’re going to meet real people here, real locals, is what a motel is also saying.

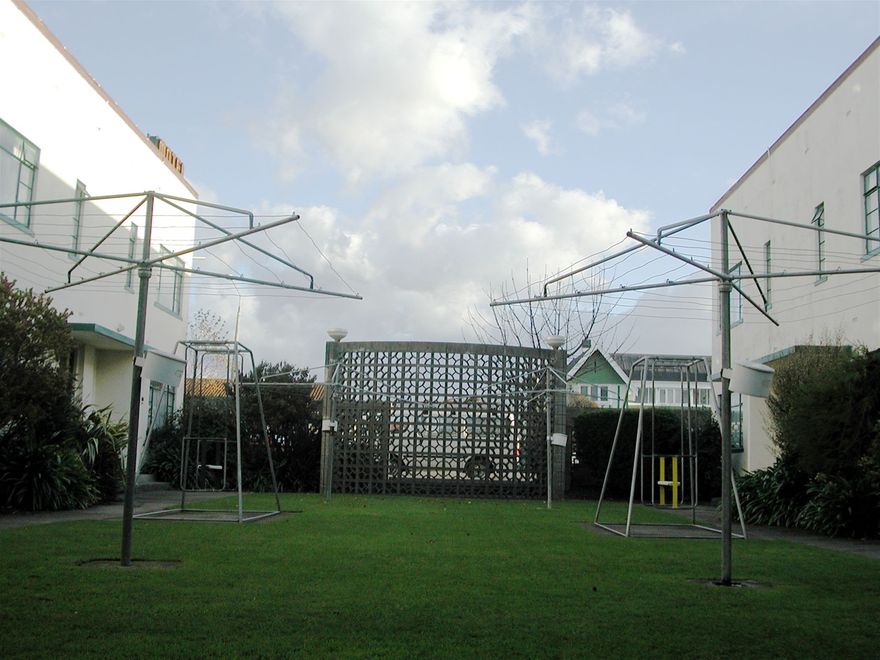

Motels that have deviated from the basic design constraints are rare. The Sandcastle, near Waikanae is one striking example; and it may be worthwhile to take a look at these differences, to better understand the norm.

Wellington architect Roger Walker designed the Sandcastle in the late 70’s, to a more unusual brief than a normal motel project would provide. Although the Sandcastle is now listed among the motels in the Jason’s guide (where it’s design singularity immediately stands out from all the other pictures), Walker says the initial idea was to create a weekend retreat. So the Sandcastle has the luxury of being able to orientate itself organically on a large site, and not be bound by the linear constraints of parallel road frontage, or a narrow urban fringe section. The address is at the end of a cul-de-sac, last property before the beach, a wee bit remote. And although this is only a couple of k’s from the main road, this location, says Walker, made all the difference.

But still, the project called for a low-cost approach – and this would be consistent with many motel developments. So Walker created a standard basic stand-alone unit, the whole made more interesting by the irregular placement of these on the generous site. So – back to Sandford’s view: decent design needn’t cost the earth, and it will always set you apart in the long run.

Beyond that, I’ve observed that there are uneasy, yet symbiotic relationships between the ‘externals’ and the privacy of your temporary little retreat in the motel room. The sign out on the road, for instance. If it doesn’t catch your eye, you’re not going to pull in. But then, once you are in, you don’t want a large neon sign looming in your window all night.

Then there’s the relationship with the road itself: without the road, the motel has no lifeline. Yet motels love to boast (sometimes unbelievably) about ‘quiet surroundings’. But get too far from the road, and passing traffic just won’t arrive. Perhaps the best is down a short right-of-way. Either way, the motel needs the road.

There’s also a strange (though thankfully not prevalent) imperative to make motels appear exotic, or aged – so our Pacific Island nation is littered with hacienda style, mock-Tudor style, and various other ersatz designs. Where does this come from? I couldn’t begin to hazard an interpretation in this brief article. But maybe there’s a cross-over anthropology-architecture thesis in there somewhere. At least, here’s hoping that future motel design in New Zealand will make it into future architecture books.

Whatever. There’s a school of thought that says something like “if it has been built by us, then it’s part of our architectural heritage.”

The only point being made here, is that this must then also include our classic roadside motel. So perhaps we should take another look at what we’ve overlooked before.

*

This first appeared in New Zealand Architecture magazine