Writing and art by Alex Stone

Something in Your Eyes and Babele, by Neil Sonnekus

A wee while ago in these pages, we noted the felling of a great tōtara within the Waiheke Community. Jim Hodgetts was way more than a favourite bus driver – and we all knew that. One of Jim’s further abilities was as a writer.

Now, his place behind the wheel is being taken in part by another writer, Neil Sonnekus. And like Jim, he’s greater than that bare appellation too: for South African-born Neil has been recognized with critical acclaim for his novel Son, and awards for his film-making and playwrighting.

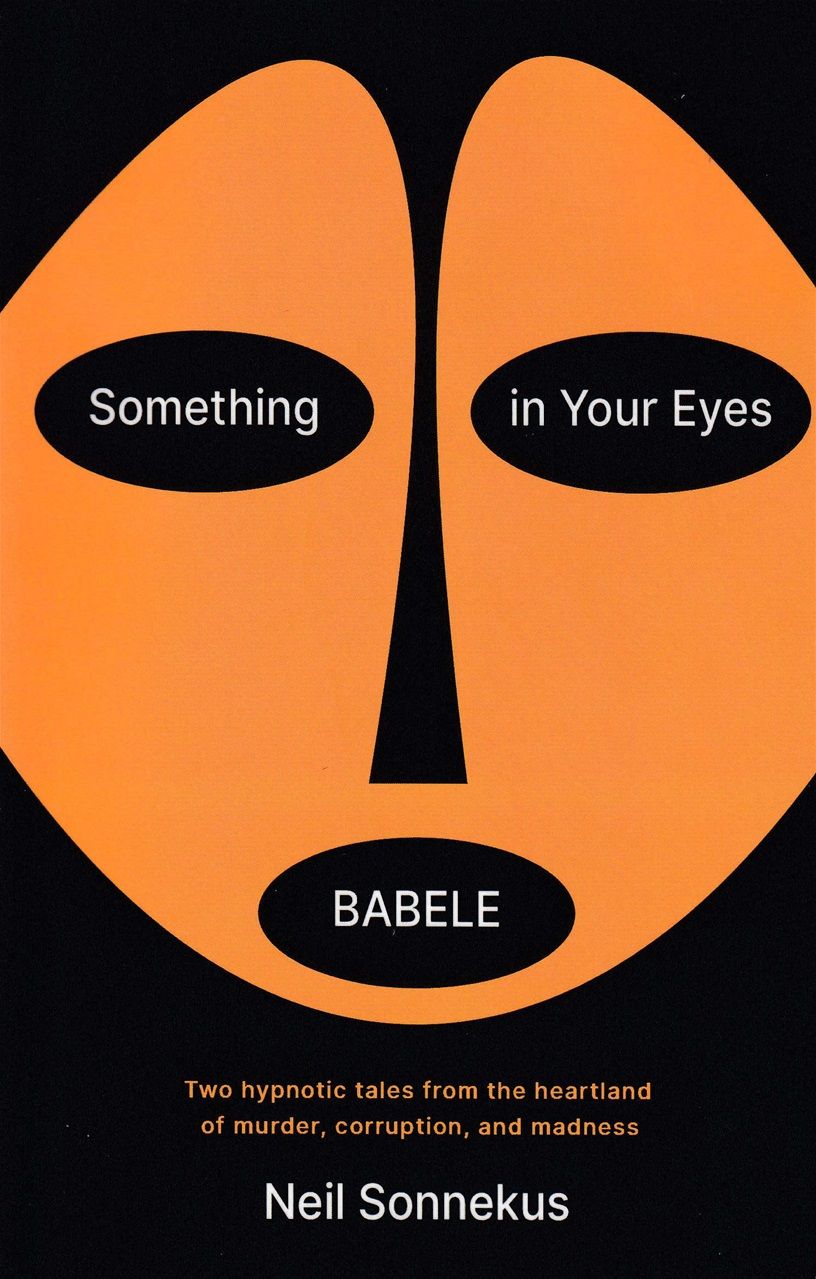

His latest offering, a book containing two novellas, Something In Your Eyes and Babele, I predict will receive a similar reception. For a start, it has a striking cover (by Neil’s son Leo) and the compelling cover blurb, ‘Two hypnotic tales from the heartland of murder, corruption and madness.’ For once, this does not deceive. I read both in one sitting.

Something in Your Eyes may at first strike the reader as mannered, in that Neil is at play with the structure – and strictures – of the pot-boiler private eye novel. But there the similarity ends; for it is rich in symbolism and authentic detail, far beyond the usual formula. From its opening line ‘Harry sat staring at the dregs of his cheap Cape wine, wishing he could smoke,’ Something In Your Eyes broadcasts its genre, intent, location and ability. I wrote in my notes on that first page “I bet it’s Tassies” – and sure enough, a few pages later, Neil confirms that yes, our classic character was indeed drinking Tassenberg. I was hooked, and read rushing through in headlong pace as the novella hurtled to its unresolved denouement. Just like I like them. The unstoppable road trip that leads us there is full of poetic prose describing the country’s ancient, and still rapidly-changing, landscape.

The writing is filled with delicious in jokes for those in the know about South African culture (just like the blockbuster movie District 9 was.) When we first meet the central figure of Something in her Eyes, Lindiwi Maqoma, we know she’s going to be a feisty character. For her name is the same as the great amaXhosa warrior chief who mostly got the best of the Boers, British and their Griqua mercenaries in the early rounds of their 100-year-long war of resistance. And when she is described in terms of being either a Dove or a Lux (soap) woman, we are in on the joke. This one finds its parallel in the distinction between ‘White Bread’ or ‘Vogel’s’ Kiwis, only in South Africa, as always, there’s a racial element at play.

Naming is one way in which the novellas are linked. They are, of course both set in South Africa, in the fertile literary ground touched by the ends of the Rainbow in the new nation’s name. The main protagonists, Harry and Hari might also be mirror images, as their similar names suggest. As Neil says, “Much like the two novellas make one book, just so they might make one person, male and female.” In both, there’s a character with the surname van As, which means ‘of the family of ash.’ In Something In Your Eyes he’s a corrupt white policeman, a stalwart of the old order (which was just as corrupt as the new); in Babele, he’s a smelly, abandoned, though musically-gifted boy from a destitute Afrikaner family. Like so much in South Africa, the symbolism is strong, if you recognise the cues. But even if you don’t, they’re there, and the writing in itself is, yes, as the cover promises, ‘hypnotic.’

One marker of good writing, I reckon, is in the clever (and memorable) naming of characters, and their subsequent building of depth from that auspicious beginning. Neil doesn’t disappoint – though I might need to help New Zealand readers (but certainly not African ex-pats) with this.

For someone in the know like me, the characters in Something In Your Eyes, are perhaps a little too conveniently drawn. But perhaps this is a result of the genre chosen for the telling of this tale. Harry Mann, the private eye, is hard-bitten, alone, he smokes, and seems to operate in perpetual hangover. Natch. And the other main characters, Lindiwi Maqoma among them, are based so closely on real ones, you know exactly who Neil got the inspiration from. Yet still they surprise us – Harry and Ruby especially. No more plot spoilers from me. I think Neil did all this deliberately, to lead us effortlessly in the story – just as we relax in the comfort of a favourite type of music. More on this music theme later.

In Babele, the hero is Siya Khoza, a name very close to that of Siya Kholisi, South Africa’s iconoclastic Rugby-World-Cup-winning Springbok captain, who out-foxed all his competitors (including the All Blacks and their coach. There’s another story in that). The Siya parallel is strengthened by the fictional Siya’s unconditional acceptance of two special children, much like the real Siya did in locating his long-lost much younger (and orphaned) siblings and adopting them.

Just like the great South African novel The Long Silence of Mario Salviati by Etienne van Heerden, Neil’s novella’s do offer challenges in the ‘lost in translation’ issues of authentic writing. This is but a minor concern, and could be tweaked in future editions – all so easy in the new print-on-demand world of publishing. Some, but not all Afrikaans and isiZulu words are italicised, thus unnecessarily (I think) identifying them as ‘other.’ Some are neatly explained in context however, such as this sentence about Harry Mann: “..but right now he wished he had a gat, no matter how anti-gun he was in general.” And some choices could have been made differently. For example: “…you could have heard an ibis feather fall.” South Africans would instead say ‘hadeda’ for the common, raucous birds. Or if they did, they’d say ‘sacred ibis’, which in this context – a hearing at the Truth Commission – would add further symbolism.

Beyond that quibble, Neil’s writing is simply terrific. His dialogue, in Babele reaches heights of immediacy, intelligence, authenticity – and of course, symbolism. There are other seminal and memorable scenes in Babele, like the urchin Anton van As in his first playing of the grand piano (the main protagonist, Hari is a travelling concert pianist); or the simultaneous singing of many national anthems in the Great Hall of Babele, under the giant golden chandelier. It’s an African Orchestra Seats, with a cast of magical citadels, semi-supernatural and very real characters, and a stage for the greatest of arts.

For both novellas offer the added bonus of an education in music. South African jazz, in the oft-appearance of real and great figures like Hugh Masekela and Abdullah Ibrahim (or Dollar Brand), but also the lesser-known, but just as gifted Moses Molelekwa and Simphiwe Dana. That they rub shoulders easily and naturally with Frédéric François Chopin and Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev is further testimony to the skill and depth of Neil’s writing. These are novellas with a unique soundtrack. The oblique allusion to Molelekwa in the final pages of Something In Your Eyes, is especially poignant, as murder-suicide among couples is distressingly common in that tortured country.

The style of Neil’s writing is an obvious nod to one of his literary heroes (and mine), the under-appreciated novelist Christopher Hope. One of Neil’s plays is an award-winning adaption of Hope’s novella the Black Swan. Both Something In Your Eyes and Babele reference Hope’s novels Me, the Moon and Elvis Presley, and My Mother’s Lovers. Most notably for their similarity in the way ironic humour is employed in truth-telling fiction. For those interested in the richness of South African literature, they’re all worth reading.

Babele is a lovely work of magic realism. Which is quite apposite, given that much of recent South African history verges on the fantastical anyway. Babele itself, the glittering city in the desert, is modelled on the impossibly real Sun City and Monte Casino complexes. It is also sited in the supposed vicinity (somewhere in the far, dry northern regions) of historical mythical cities such as Monomatapa and Rider Haggard’s Kukuanaland in King Solomons’ Mines. In modern South African literature, there are similarities, deliberate I reckon, between Babele and the bizarre but truly African locations of Magersfontein, O Magersfontein by Etienne LeRoux , and The Empire in JM Coetzees’s Waiting for the Barbarians. Babele is in stellar company.

That far North West is also the place fugitives run to in so much of South African story-telling is important too. In André Brink's An Act of Terror, for example, and in David Kramer’s epic song The Ballad of Koos Sas. Connections like this are everywhere in both of Neil’s novellas. Indeed, ‘Allusion and Connections’ could be an alternative title to this pairing. These tales ‘from the heartland of murder, corruption and madness’ have direct relevance to all of us in the here and now – wherever we may be.

For those connections are universal: Neil’s playfulness with the detective novel form in Something in Your Eyes; and in Babele, the eternal story of the returning Prodigal Son – only now it’s Hari, a woman, with all the symbolic weight (in Afrikaans, ‘bagasie’) she carries. These novellas are readable and relevant everywhere; and especially so In New Zealand, given our long-standing, familiar (if fraught) relationship with South Africa(ns).

That she carries it so well is testimony to how well the story-teller does too. Well done to our new island writer (and bus driver) on this achievement! The big shoes are indeed being filled; and we as Waiheke Islanders, are all beneficiaries.

The book is for sale at the Saturday morning market at the Lasavia stall (in the hall) under the auspices of writer and publisher, Mike Johnson. The book can also be bought online from the likes of Amazon, and for retailers, from Ingram Spark Australia.