New World, new views: a look at systems from the vantage of my cave

Once upon a time, a man his partner and children, (and their dogs, too) looked out from the mouth of their cave home, and saw a world to live in.

There were seasonal pulses of scarcity and abundance, sure, but with enterprise and effort, there would be game animals to hunt, and roots and fruits to gather. And then there was the competition from the other human species – but that was not to last.

Our man and his family, and their descendants, made steady progress. They got better at doing what they had to do, over time. It was only when they mostly became tied down by a reliance on crops, that, for a long while their lives became tougher. But the fittest survived, made more people, kept on striving, and here we are.

Now upon this time, I look out at the world from the comfort of my COVID-19 cave, and what do I see? I see a near world on the quiet; a community cautiously venturing out as if there’s some great fear at large. Which of course there is.

Looking – or rather listening – wider, I learn of established systems of administration, government and business taking a gut punch, confused and struggling. And of their instinctive, cornered reactions. I hear on the news that Air New Zealand, that recently great and profitable business, despite a massive cash grant from the government, will be laying-off 3,500 staff. What, I wonder will they do when they need these people again? When business returns to normal? Or if there will ever be a normal again.

I see a nation all hushed and insecure as if some inexplicable force of fate has demanded that we slow down our hectic pace, and sent a virus by way of practise. Naturally, this has led me to take another look at what, just till recently, were our fundamental, imperative systems. How we chased material advancement, and ever-increasing comfort and convenience. How we shopped, endlessly and as if there would be no limit to it all. How we mostly drifted away from religions. How we counted our success in things and money. And how we had – and now have even more so – become reliant on a webworld seen through the window of the laptop screen.

The result, like one of those Magritte paintings of a window and a constructed view through it, is an outlook that says simply, Things are not what they seem. And like the repercussions of the surrealists’ worldview, our view may be forever altered. In this lull, there’s time to consider what has built our society, our current culture and our economy. And how these foundations may not be as secure as they seemed.

Which leads to the thoughts: What is it we have built as our meta-system? What can governments do in the face of an unseen invasion? And how does that affect our markets, our economy, our lives? What happens to income? To money, and the ability to make it? What is the essence of capitalism? How come it is so easy to arrest? And, has it had its day? Its pure dictionary definition is “an economic and political system in which a country's trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.” In practise this has come to be accepted, sort of, that as part of the capitalist system as we know it, is the ability to make money from money (considered a sin in the Muslim world), and the resultant fact that the rich get richer while the rest just hang on.

Scarcity is a central driver in the operating of markets in the capitalist system, for it determines prices. Of course, scarcity can be manipulated for profit advantage. One example of this is De Beers Corporation’s monopolising and selective marketing of the world’s supply of jewellery diamonds, to maintain their high value.

Hart Buck, a statistician at the Toronto Dominion Bank says “The basic idea of capitalism is that if we are left free to choose what we want most, we’ll get the most of what we want.” But right now, we mostly have vastly reduced freedom of choice. And as we have seen, even in normal times, that choice is not always unfettered.

Capitalism has evolved to depend on constant growth in the economy. The proponents and beneficiaries of the system are adamant that we need growth to survive. One of the biggest fears of capitalist economies is recession, defined as ‘negative growth.’ But endless growth is a futile dream. The choice thing may be fine, but there is the irrefutable observation that pure capitalism can and does lead to a continuum of exploitation, depletion and eventual extinction of resources. And taken in a wider view, this can trigger starvation, pollution or environmental collapse – which hardly gives people choice then, does it?

The earth, our planet, large as it seems, is a finite system. This may seem like a statement of the obvious. But it seems to have eluded the designers and proponents of capitalism. Earth only has so much in the way of resources. It has only two inputs: solar energy, and that of the gravitational force of the moon that power the tides in the oceans. The deposits of coal, or other fossil fuels, for example can, quite simply run out if exploited endlessly. Then what?

The defenders of capitalism will respond that human ingenuity, which has always been rewarded in this system, will be inspired/motivated/incentivised to invent other methods of energy transfer. And you could say this is happening right now, with the advancements in photovoltaic energy systems harnessing solar power, and the rapid improvement in storage mechanism through improved battery technologies and design.

To look at our supporting ecosystems as essentially and ultimately finite, then it follows that eternal growth is self-destructive. An analogy would be the unstoppable proliferation of cells in a body that is the driving force of cancer. And we know the disease does not have good outcomes. Paul Mason, a writer for The Guardian newspaper, and author of the book Postcapitalism writes: “As with the end of feudalism 500 years ago, capitalism’s replacement by postcapitalism will be accelerated by external shocks and shaped by the emergence of a new kind of human being. And it has started.”

He cites three factors in the development of information technology in the last generation that are pivotal to this change. “First, it has reduced the need for work, blurred the edges between work and free time and loosened the relationship between work and wages.

“Second, information is corroding the market’s ability to form prices correctly. That is because markets are based on scarcity while information is abundant.” The giant tech companies that have developed, he says, cannot last: “By building business models and share valuations based on the capture and privatisation of all socially produced information, such firms are constructing a fragile corporate edifice at odds with the most basic need of humanity, which is to use ideas freely.”

In a way, it’s a case of capitalism destroying itself. The e-business model, built on the premise of holding, monopolising and controlling data – and charging for it – simply cannot last.

And third, “we’re seeing the spontaneous rise of collaborative production: goods, services and organisations are appearing that no longer respond to the dictates of the market and the managerial hierarchy.”

Take a look at Wikipedia, he suggests. It’s the largest information product in the world, yet it has no private profit motive or outcome, being the product of an army of volunteers. It has already destroyed the encyclopaedia industry, and deprives the advertising industry of billions of dollars.

To look at it from another perspective: while capitalism relies on the exploitation and manipulation of scarcity (often by remote elites), and rewarded unequally by hard money, the currency of postcapitalism is centred on free time, networked activity and free stuff. The real problem to the old ‘industrial capitalist’ system, is that this new wave of information cannot be adequately assessed under capitalism’s playbook.

The value of intellectual property for instance, is always just a guess. And the knowledge content of products – smartphones, for example – is way more than their intrinsic physical worth. This new wave of ‘cognitive capitalism’ is predicated on dynamics that are essentially un-capitalistic.

The proliferation of information in our online, connected, digital age, is close to zero. Information is incapable of being controlled, owned, exploited, and priced. So where is the ‘profit’ in that? Profits is suddenly sounding like an antiquated and useless concept.

The irony is that the sharing of information was – is – seen as a social good. That’s why the internet was gifted to the world by the US military, for free. The power of knowledge now lies with all of us.

Karl Marx envisaged this exact scenario in a piece written in 1858, The Fragment of Machines, which was published only in the 1950s. (As an aside, given what we know that the application of Marxism was to become – a theory of exploitation based on the theft of labour time – this is revolutionary for an entirely different reason.) In Fragment, Marx wrote that the information economy would “blow capitalism sky-high.”

Besides these epic challenges to capitalism, there are other parallel crisis points in play right now. The effort to slow-down or minimise climate change by ‘de-carbonising’ our production and transport, indeed our very living systems; and dealing with demographic timebombs, like over-population, forced mass-migration, and the international conflict between haves and have-nots (who have populations dominated by the elderly and youth, respectively). We have to deal with these simultaneously with our rewriting of our established economic tenets.

A previous example of essential change that we can look to for guidance is that when feudalism was changed into capitalism. Feudalism was system based on obligation. Capitalism was based on scarcity, and the free market’s manipulation of this. Post capitalism (we don’t yet have an independent term for our new age) is predicated on abundance, and free and universal access to information. Feudalism, and its agricultural economy foundered on environmental limits and the great demographic shock of the Black Death. Suddenly there were too few workers.

The subsequent rise of merchant capitalism was built on the backs of the slave trade, improved shipping, and newly-discovered resources to be exploited in the New World. But that model seems to have run its course.

Now the internet is everything: it is the ships, the ocean, the gold – everything in one accessible place. What’s the new system to be called? Mason suggests ‘Project Zero’, based as our new socio-political-economic system will be, on “a zero-carbon-energy system; the production of machines, products and services with zero marginal costs; and the reduction of necessary work time as close as possible to zero.”

A core challenge in the world facing us will be to decide, and to act, on what’s important and what’s urgent. Sometimes an issue is both (like climate change), but often the two are separate.

Urgent issues (like food security in a crisis like COVID-19) must be addressed simultaneously with important stuff (like restructuring work to remote, and modular units). There’s a contradiction in place now between scarcity (possibly of food, but certainly in the capitalist way of keeping products and services commercial), and great and freely accessible abundance (information on the web). Mason sums up the task of integrating the two: “We need more than just a bunch of utopian dreams and small-scale horizontal projects. We need a project based on reason, evidence and testable designs, that cuts with the grain of history and is sustainable by the planet. And we need to get on with it.”

The current COVID-19 international crisis will have a hand in hastening capitalism’s demise. Already, some ideas that are anathema to classic capitalist thinking – like a universal basic income (UBI) – are being considered and implemented. Under duress, yes, but UBI is now a realistic option, and being widely considered, even if only as a temporary measure at this stage.

One thing is certain: the lockdown of societies around the world has halted capitalism frenetic growth pattern. In this hiatus and its aftermath, I reckon it’s time to look carefully at our other options.

Jokers in the pack

The problem with political jokes is they get elected. Or so they say. If we look at two democracies close to us, this may well be the case.

Is there anything fitting of the gravitas of leadership, in the figures of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson? The problem is, they don’t see themselves as the buffoons they are, and instead live in a deluded state of self importance.

Strictly speaking, of course, neither was actually elected: Donald was a fair way behind in the national popular vote, and Boris got to power through internal party machinations.

But it’s true – too often, jokes do get elected. Where’s the precedent in this? Perhaps if we look at that older democracy, Iceland, we may find an answer. Jon Gnar is an Icelandic comedian. He started a joke party, primarily to satirise Iceland’s reaction to the Global Financial crisis, and then surprise, surprise, he was handily elected as mayor of Reykjavik, the country’s biggest city. By all accounts he did a decent job of it. And best of all, displaying an absence of hubris that Boris and Trump could well emulate, he decided not to stand for re-election. One term was enough. The funny-ness lasted only so long.

In Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenksy was elected president, winning in a landslide with 73% of the vote against the incumbent, in a national election in April 2019. Zelensky entered the race with high recognition – he’s the star of a long-running comedy series, Servant of the People, on TV that has him acting the role of a humble fellow (a school teacher) who sort-of accidentally becomes the president after a political rant of his goes viral on social media.

Now life has followed art, laughingly, and he’s become the real thing. He said he wanted “to bring professional, decent people to power.” Mostly, his real life campaign was conducted on social media, with Zelensky clearly avoiding the traditional routes to power. Trouble is, he has inherited severe problems in the country. Russia invaded and annexed the Crimea peninsula region of the Ukraine in 2014. A complicating factor is that – apparently – the majority of people in the Crimea wanted to be connected to Russia, rather than the Ukraine. The lumping of the Crimea with Ukraine in 1954, as part of a Soviet Republic had long been contested by the people of the Crimea, and especially in the city of Sevastopol.

Zelensky’s campaign was based on his personal charisma, and his anti-corruption message. His slogan: “No promises, no apologies,” was a neat cop-out of the usual political grandstanding. He promised to rid the country of its dependence on Russian oligarchs (is there any other kind of oligarch?). To complicate matters, Zelensky himself is more Russian than Ukrainian, having grown up in a Russian-speaking environment, and conversing in Ukrainian only as his second language. Still, he has said that “the border is the only thing Russia and Ukraine have in common.” In July 2019, in the parliamentary election, his Servant of the People Party won the first single party majority in Ukraine’s post-Soviet history. So it seems they’re not going anywhere soon. He’s talked to Putin on the phone, and has tried to arrange an exchange of prisoners held by both side, which has happened. He’s publicly stated that he considers Putin “an enemy.” This real world he finds himself in, is a far cry from comedy, I’ll say.

Marjan Sarec, a satirist was elected Slovenian Prime Minister in August 2018. I wonder how people knew whether he was talking seriously or sarcastically, during the campaign. A valid question.

Jimmy Morales, the current president of Guatemala was previously a comic actor.

So they’re out there, the political jokes that get elected. But I reckon they find the reality a far cry from the comedy they’d prefer. That’s life, I suppose.

Way Ahead

Among the two dozen hopefuls now vying for the Democratic nomination to run for the US presidency, I doubt if there are any as iconoclastic or as forward-thinking as Victoria Woodhull.

She ran for president way back in 1872. That she was the first woman to pitch for the role is in no doubt – she was that far ahead of her time.

Women couldn’t even vote in the USA in those days. But Victoria argued irrefutably that the constitution had guaranteed rights to “all citizens.” Of course. In fact it was only the 19th amendment to the US Constitution, enacted at last in 1920, that afforded the vote to women.

Anyway, Victoria Woodhill was an unusual case. She certainly did not allow any of society’s existing impediments to women to stand in her way. She was born in 1838 to almost-fictional circumstance in the small frontier town of Homer, Ohio: Victoria Claflin was the seventh of ten children, her mother Roxy illiterate and illegitimate, her father Rueben ‘Old Buck’ a con man and genuine snake oil salesman. Her early childhood was tough in the extreme. Her parents hardly fed her, and her father abused her. By age eleven, she had only three years of schooling. Her father was run out of town for burning down his own mill in a fraudulent attempt to gain the insurance money. When Victoria was just 14, she met Canning Woodhull, a bush doctor who treated her. (In those days, Ohio asked for no qualifications for someone to pose and practise as a doctor.) Some say Woodhull abducted her. In any event, they were married a few months after Victoria’s 15th birthday. She soon found Woodhull to be an alcoholic and a womaniser. She had to often fend for her own, while looking after two children, Byron and a daughter, Zulu (later called Zula).

Without too much ado, Victoria divorced Canning, and professed herself to be a proponent of ‘free love ‘ – that is, believing women could choose to love who they would, rather than being tied to horrible marriages. She reckoned she had the right to change her mind. She began campaigning vigorously for women’s rights. She was also a spiritualist medium. Later she also spent some time debunking and exposing those she considered fake spiritualists.

In about 1866, she married again, to Colonel James Harvey Blood, a Union Civil War veteran. He was the city auditor for St Louis, Missouri. Not shy to try something new, in 1870, she and her sister Tennessee (Tennie) then became the first female stock brokers on Wall Street in New York. They gained a headline in the New York Sun newspaper – ‘Petticoats Among the Bovine and Ursine Animals.’ (Bulls and bears, geddit?) She and Tennie made their fortunes here, developing a portfolio of big-time clients, including the millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt, who admired Victoria’s skill as a medium, and seduced Tennie.

The sisters used their money to found a newspaper, called the Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly, which grew to a circulation of 20,000. The paper was primarily used to promote Victoria’s run for the presidency, but also courted controversy by publishing the first English version of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, and articles on free love, sex education, women’s suffrage, spiritualism, short skirts (yikes!), vegetarianism, and licensed prostitution. The newspaper had a national exclusive in outing a famous churchman, Henry Ward Beecher, for adultery.

A heady mix. Which brings us to her campaign to be president of the USA. Nobody really took her seriously, mostly because she was younger than the stipulated age of 35 (still valid) to be eligible to run. As part of her campaign to promote suffrage, Woodhull testified before the House Judiciary Committee, arguing that women already had the right to vote — all they had to do was use it — as the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution already guaranteed the protection of that right for “all citizens”, not just men.

For her campaign, Victoria nominated (without letting him know) as her running mate, Frederick Douglass, an extra-ordinary character himself. Douglass was a black man and ex-slave who had escaped the south, and though strength of character and the power of his oratory became a famous figure in Washington, and later an advisor to President Ulysses Grant.

Victoria ran under the banner of the Equal Rights party. Just before the election, Victoria and Tennie were arrested and imprisoned for allegedly running an obscene newspaper. In the election, as expected by many, she received no electoral college votes. In the whole country, only one man admitted to voting for her.

She tried running again for the presidency in 1884 and 1892. But still, no joy. In 1877, after the death of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the sisters were paid by William Vanderbilt (fearing they knew too much about the financial affairs of his estate), to leave the USA and emigrate to England. They took the money and left.

In England, Victoria married a banker, John Martin, gave high-profile lectures on subjects such as ‘The Human Body, the Temple of God’, and started the magazine The Humanitarian which she ran with her daughter Zula.

Victoria Woodhull’s remarkable life shows that there should be no limits to life’s experiences. And that the mores of society should never set such limits. But sometimes, society take a seriously long time to catch up with the front-runners of radical thinking. And in the meantime, The USA still waits for its first female president.

Miracle of Wörgl

In these days of miracle and wonder (not), when our collective orbit has been reduced to the home office, larger questions abound.

Like, what is the future of money? Can it still work? Or, can it work in a different way? Who gets to give you money, when you’re sitting in lockdown? Are the rules of capitalism set in stone? What if money had a use-by date? What if keeping money had no advantages?

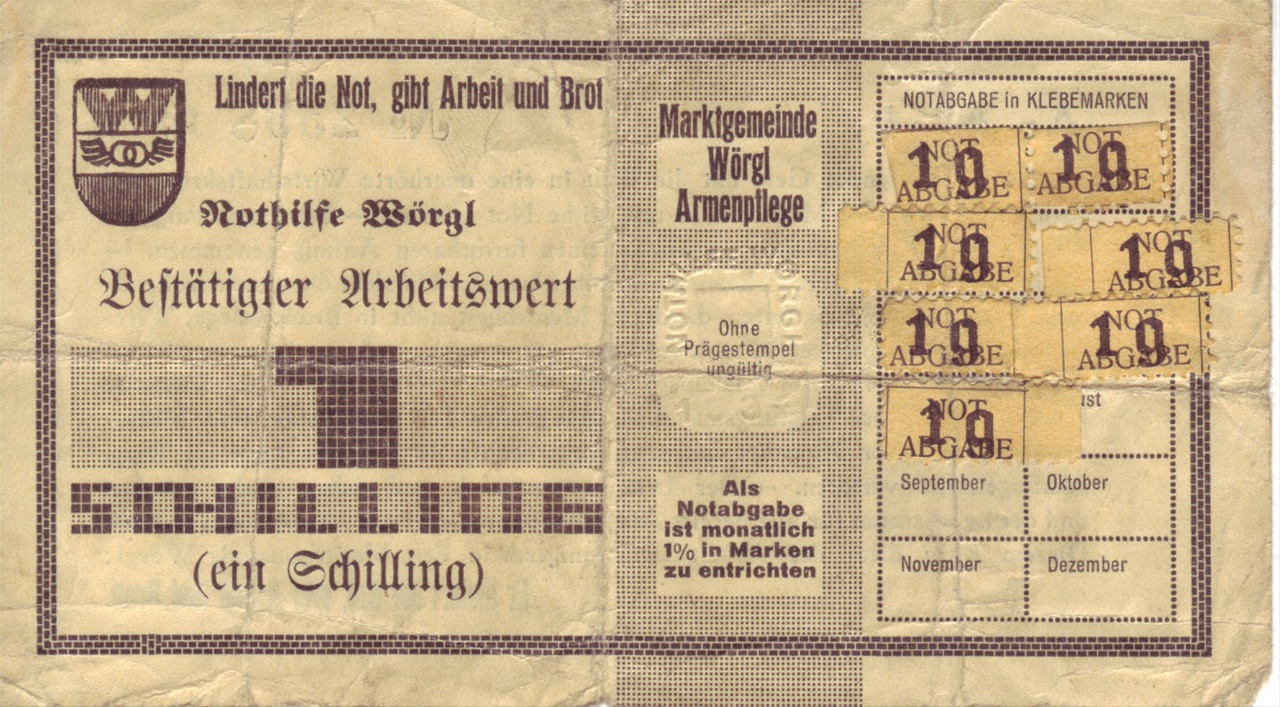

Allow me to introduce the Wörgl Mircale – or Experiment, depending on your point of view. Wörgl (groovy name) was a wee town in Austria that tackled the Great Depression in a novel way.

It broke all the rules of standard capitalist economic theory. Wörgl printed money. They gave it to the townsfolk, for free. Whaat? You may say, but it worked. Truly.

Here’s how it happened. Like small towns everywhere in the Great Depression, Wörgl had people sitting around, out of work. And shops with no customers. The usual story.

Wörgl had a population of 4,216. Being a railway junction, the railway employed 310 people in 1930, but by 1933 the number had plummeted to 190, following the transition to electric locos. The cement plant in nearby Kitzbühel employed 50 workers in 1930, but by 1933 only 2. The Zipf brewery sacked between 10–14 workers from the previous 33–37. A cellulose factory had once employed 400 workers. In 1933, just four men were there, idly guarding idle machines. Farmers, a third of the work force, could hardly sell their products at depressed prices.

But the town’s mayor, Michael Unterguggenberger (off-the scale groovy name!) suggested something radical. Let’s print our own money. The experiment began on the 31 July 1932, with the issuing of ‘Certified Compensation Bills’, Wörgl’s own currency. It was cheerfully named Freigeld – or as Stamp Scrip, if you will.

Result: a boom in local government projects, and a corresponding increase in employment and economic activity not just in the government sector, but throughout the town. People had to spend their free money. And spend it they did, on contractors to do building, on food and furniture and stuff in the local shops, to pay farm workers to plough the land and bring in the crops. People paid their taxes.

Wörgl money worked differently. It had a use-by date. So it didn’t pay to accumulate it. You had to spend your allocation by the end of the year – or it would decline in value by 10 per cent. In dry economic terminology, this is called currency demurrage. “Whatever,” said the people of Wörgl. And carried on spending up large.

Irony, bigly these days, is that Wörgl banknotes are now seriously collectible items – worth a fortune, especially those with the devaluation stamps attached).

Anyway, Wörgl money had the effect of jump-starting the local economy. Things started humming. The money had to be used, you see. Where’s the problem in that?

Now, money as we know it, was invented to accumulate in value. For those of a religious bent, that is reflected in usury – the practice of lending money at unreasonably high rates of interest, so the money you give out comes back as more. That’s what caused Jesus to lose his cool at the Temple on the Mount. And in the next Abrahamic religion that came along, Islam, the charging of interest came to be seen as sinful.

People further than Wörgl’s town limits sat up and took notice; among them such luminaries as French Premier Edouard Daladier and the economist Irving Fisher. The “miracle” gained notoriety, and other towns wanted to copy the experiment hoping for similar success. Nearby villages even arranged to accept each other’s scrip. In June 1933 Mayor Unterguggenberger was the star at a presentation in Vienna for 170 Mayors—they were intrigued on hearing reports from Wörgl. Among the attendees, some opined that it would be a go to introduce "magic money" in their communities too.

But the rich and powerful didn’t like it. Wörgl did not fit their script. It was supposed to be their schtick to hold great sums of money (and therefore power), and for this money to accumulate. The poor folk, like those in Wörgl, were supposed to borrow money at the rich folks at exorbitant interest rates.

So, under pressure from the wealthy elite, the Austrian government capitulated. The Wörgl miracle was murdered by the Austrian National Bank on 1 September, 1933.

Looking back on the whole Wörgl thing, contemporary economists say the Miracle couldn’t last. They use dry and dreary and self-serving arguments like, “any threat to centralized control is a threat to the money power”(Yeha! Right on!); or “Wörgl could not legislate or enforce monopoly legal tender, so the demand for the scrip is partially attributable to the need to pay taxes” (so what?); or “In a matter of days the national scrip held as backing in the bank would have been exhausted” (but who needs banks anyway, when you get free money?) or “Wörgl was not a miracle, but an example of Keynesian spending given incentive by Gresham’s Law” (blah, blah…).

But then you could also say, the ‘experiment’ of capitalism as we know it – endless growth and resource extraction, the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer – can’t last anyway. And now we have a new window on this capitalism deceit. How come, we say, the economies of the world collapse when people buy only what they need?

Come back Wörgl. We need you now.

Pirate citizen - a short-lived republic

The idea of a pirate republic has a kind of oddball (blackball?) appeal - if only for bizarre reasons. Curiosity is aroused.

What would the services be like? Would the rubbish be removed regularly? Would taxes be fairly and evenly spread? What would the dress code be? Would there be banks, or would all monies be buried around the place?

And what, for instance, would the fate of women be in such a place? Or bouncing babies, squalling toddlers, energetic kids, or sullen teenagers, for that matter? Old age homes, retirement villas - where would they be?

One thing is for sure - the harbour would have been filled with the fastest sailing ships, but I imagine they'd all be worried a neighbour would come commandeer the vessel and sail away. Such is the nature of pirates.

A pirate republic did exist in the late 17th century, was named Libertalia, and was located in Diego Suarez Bay at the northern tip of Madagascar. Or on one of the nearby islands – we're not sure exactly.

But this was a real functioning settlement, 'tis said, with a population of at least 1,500 people, and it was in business for 25 years. So goes the story.

Libertalia was established by Captain James Misson, of the ship Victoire. Apparently, Misson embarked on his career under the influence of a "lewd priest", one Domsignor Caraccioli.

But can you believe it? It could all be a fiction by Daniel Defoe, written as A General History of the Pyrates under the pseudonym Captain Charles Johnson.

"Pirates were a unique race, born of the sea and of a brutal dream, a free people, detached from other human societies and from the future, without children and without old people, without homes and without cemeteries, without hope but not without audacity, a people fro whom atrocity was a career choice and death a certitude of the day after tomorrow." So said another writer, Hubert Deschamps in his book about this strange episode in history, entitled Les Pirates A Madagascar; and all of which points to the notion that a pirate society would be.... unbalanced, to say the least.

But then, pirate ships were apparently run fairly democratically. Actually, very democratically in relation to the HR practices in place on navy ships of the period. And there were (very few, admittedly) women pirates. And pirates did release slaves , sometimes, when they captured a slaving ship.

The core population of Libertalia, goes the story, was a group of slaves from Angola, recognised in a prize ship by the pirates, freed and displaced to Madagascar.

Ironic too, that the flag of Libertalia was, reputedly, just white. The citizen pirates of the place renounced their previous nationalities, called themselves Liberi, and spoke a language that was a melting pot of African languages, stirred with French, English, Dutch, Portuguese and native Malagasy.

We are told, too, that the pirates settled down to become farmers, holding the land in common - "no Hedge bounded any particular Man's Property." Prizes and money taken at sea were "carry'd into the common Treasury, Money being of no Use where every Thing was in common."

Sounds good - or at least it makes a fine story. What is history but a collection of stories of differing veracities? Here's one at least worth listening too - even if it aint 100% true.

Now you can go to Libertalia - it's a fancy resort hotel supposedly on the site, or you can play the board game. Either way, you'll probably escape the harsh realities of real pirate life.

Best case country

Imagine a country where the best and most effective laws of the most progressive democracies of the world were all working in that one place. It would become the model for a fairer world.

This special country would, say, take on the environmental laws of the leading European powers, like Germany.

It could avoid the cult of individual leadership in the way Switzerland does, by not having a single prime minister, but a revolving chairmanship taken from senior cabinet ministers. This model country could also apply the representative democracy that Switzerland practises, where the citizenry is habituated to participating in almost-weekly referenda on just about every topic under the sun.

We could apply the freedom of speech, association and religion ethos as demonstrated by Denmark, New Zealand, the USA.

As for heritage issues, we’d be as on to it as the UK.

Compassionate euthanasia laws could be modelled on those of the Netherlands.

Social security could be as good as that in Norway, and we’d also take on that country’s incentives towards a change-over to zero-emission vehicles.

In our best-case country, it would be as difficult as it is in Singapore to own a petrol- or diesel-powered vehicle.

Restrictions on individuals owning assault-style automatic weapons would be the same as in Australia.

Commitment to the human rights of refugees would be as advanced as that in Germany.

Tax laws would ensure super-wealthy individuals and multi-national corporations pay their fair share, just as they do in Sweden.

Government-subsidised tertiary education would be as comprehensive as it is in Norway. The universities would be as good as the top British and American ones are.

Free health care would come to you, just as it does in Canada.

Artists would be encouraged, just as they are in the Netherlands (there, if you can demonstrate that you’re a practising artist, you get a living wage just to keep on working, in exchange for supplying a set number of paintings to be used in public spaces and buildings).

Retirement income from the state would allow ageing in dignity, like it happens in Finland.

Would a universal basic income be supplied? It has been trialled on a short-term basis, and in limited areas in some countries (Canada, Finland, Namibia, among others), but nowhere is it official government policy – though some forward-thinking people say it will have to be done in a ‘post-capitalist’ world.

In this best-case country, I’m still undecided how voting laws would work. Australia has compulsory voting, so do Belgium, Switzerland and Uruguay. But then, so does North Korea (I imagine with a severely limited choice), and the Congo. Perhaps our ideal amalgam country would have freedom to choose to vote, and a highly-developed civil society, like the Netherlands and ourselves – though we could certainly do more to educate teenagers about adult responsibilities.

Anyway, that approach to voting should pave the way for free and fair elections with a consistently high turnout. Only we don’t get the high turnout we should have in this country, especially on local government elections.

What about freedom of movement put in place by open borders? The European Union has had this in place for some time, and you could say the citizens of those countries have (mostly) benefitted from this. That’s why Brexit is so widely seen as a silly, backward step. Our travel relationship with Australia is pretty easy too.

Imagine a country where the best laws from around the world are together in one place. Does such a country exist? Some do come close.

And the good news is that we the good folk New Zealand, are living in one of those almost-alright places. How lucky are we?

All we need then, is to appreciate this, and strive to make what we can better, and hold on fiercely to the freedoms and privileges we have.

Esperanto

Understanding others It’s one of the oldest stories we have: how those that speak an unintelligible language are defined as ‘the other’. Mutual understanding between peoples can only begin when we understand each others’ actual words. Their stories, legends, metaphors, proverbs.

Too much, it seems – including, often, humanity itself – is lost in translation. True, the world is slowly edging towards just a few mega-languages. And many smaller languages have gone, are going, extinct.

Is there anything like a universal language? English is probably the widest understood – though most often as a second language.

But there are still many millions of people out there who cannot, and will never, understand or make sense of each other.

Idealists used to think we could all learn to literally speak the same language. That was the idea behind Esperanto, the most successful (relatively) of the ‘international auxiliary languages’ – as they are known.

The fact that there are a number of them underscores the futility of the cause.

Esperanto was devised by Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, who was born in Poland in 1859, and who grew up dreaming of a world without war. If we all spoke the same language, he reasoned, we would never dream of taking up arms against each other. He started working on his international language while still at school. ‘Esperanto’ means in its own idiom, ‘one who hopes.’

As a child, Zamenhof was bilingual in Yiddish and Russian. His father was a teacher of German and French, so he took those languages on board too. At school, Ludwing learned Polish, Belarusian, and he also studied Latin, Greek and Aramaic. He later learned some English and Italian.

By the time he was 21, Zamenhof had completed the first part of his project, a work entitled Lingwe Uniwesala in which he laid out the foundations of what has been called proto-Esperanto.

He was diverted from his task by going off to study medicine in Moscow and Warsaw. While working as an ophthalmologist in Vienna, he started promoting his international language more widely.

In 1887, he published, in Russian, International language: Introduction and complete textbook, under the pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto (Dr Hopeful).

In 1905, he put out the definitive guide to Esperanto, Fundamento de Esperanto, and set about organising congresses to advance the language in Europe. It grew rapidly in the Russian Empire and in Eastern Europe.

There’s been an annual international Esperanto convention somewhere in the world since 1905 – except, tellingly, during the two world wars.

The Nazis and the Soviets tried to suppress the language, and punished those trying to learn and speak it. Imperial Japan forbid the use of it. The socialists fighting in the Spanish Civil War used it extensively, but it was forcibly repressed by the fascists. I suppose it’s obvious that extreme forms of nationalism have no place for an international language of community.

Zamenhof was aware of the challenges his language faced. At the Esperanto conference in Cambridge in the UK in 1907, he said "we hope that earlier or later, maybe after many centuries, on a neutral language foundation, understanding one each other, the nations will build ... a big family circle."

Still, there are now around two million speakers of Esperanto in the world, making it the most widely-practised constructed language. Esperantujo is the name for places where it is spoken. Its devotees have now partially given up on the idea of it becoming an international common language, and instead see it at the voice of a "stateless diasporic linguistic minority" based on freedom of association.

Some people try to learn Esperanto for the fun of it, or as an aid to learning other languages. (Zamenhof has as the first of three goals, "To render the study of the language so easy as to make its acquisition mere play to the learner." You can learn Esperanto online (Google Lernu!). Wikipedia has no less than 263,000 articles in Esperanto. It counts as a language on Google too.

The New Zealand Esperanto Association was founded in 1910. It now has the status of a charitable institution.

But I say, before we take on the learning of an international language, let’s learn the languages of our nearest compadres first, or perhaps that of our forebears. If I was minister of education in this country, I’d try get it done that every school student learns English, te Reo Maori, and one other language. Multi-linguilism has been proved to have many advantages, in other forms of study. We’d become a clever, more empathetic people as a result.

And then after that, we can go give comrade Zamenhof’s language, Esperanto, the ever-hopeful single international language, a go. How about it?

Democracy

Democracy, it has been famously said, is the worst system of government – except for all the others.

Those of us lucky to be saddled with some from of democracy, we muddle along within its effects – the vagaries of the voters, strange coalitions, or some special rules made up for our particular country. But hey, democracy is what we got, and we make the best of its oddities.

The biggest democratic election is history has just wrapped up in India. (This written in late May 2019). Nine hundred million people were eligible to vote, and the turnout was 67 per cent. The election was so huge it was staged over two weeks. (Imagine the logistics if India had compulsory voting!) The result, announced on 23 May revealed that the Bharatiya Janata Party, led by Narendra Modi, won 303 seats, further increasing the majority it had last time.

Modi and his party were accused in the campaign of fermenting religious divisions, but in his acceptance speech, Modi said: “even if the government is built with a majority, the country runs with everyone together. We will walk with everyone together.”

In that seething melting pot of a country, democracy must be a messy road to follow, but somehow it works, despite the fervour of the campaigns.

This last election was notable for the highest level of participation by women. There are 545 seats in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Parliament of India, and the elections take place every five years. The Lok Sahba has its own television channel, for those invested emotionally in politics in the country.

A strange feature of the election was the dominance of the BJP party, which now faces a collection of 13 opposition parties and one independent. Most democracies at least have two main options to go for – but not so, It seems in India. Because the opposition is so scattered, the parties so minor, there is no official leader of the opposition. Probably not a good thing in such a huge democracy, but there you go.

Australia had their tilt at democracy just recently as well. Because they have compulsory voting, one feature of their elections is the so called ‘donkey vote’, where reluctant voters just go eeny-meeny-miney-mo in placing their vote. Some times the victories (like that of Tony Abbott) are within a margin for error provided by the donkey vote.

The latest result, the election of Scott Morrison at the head of the Liberal/National coalition was surprising in that they had been consistently behind Labor in the polls for the entire campaign. So this begs the question: how do we get to understand the will of the people, if polls get it wrong? But the people have spoken through this election, so we must wish The Aussies well.

Also in May, South Africa held its sixth election since the end of Apartheid. As expected, the African National Congress won, but with a declining majority – 57%, down from 62% in the 2014 election. The form that democracy takes in South Africa is closed list proportional representation, so no-one votes for a person. All votes cast are party votes only.

Does it work? Well the country has struggled lately on many fronts, including rampant unemployment and corruption. The over-riding feature of the South African electoral scene is that the ANC – the liberation party of Mandela et al – will dominate for a generation. There are millions of people who will vote for no other party until they die.

But of concern is the rise of the firebrand Economic Freedom Fighters party, led by Julius Malema, which promises a scarcely-believable nirvana for those dispossessed. There’s enough desperation in the country for Malema to make way.

Still, the leader of the ANC, Cyril Ramaphosa, promised a “new era” for the country after the election (meaning, hopefully, with less corruption). If there’s one democracy we all look to, it’s the United States of America.

But it’s in the midst of a constitutional crisis right now, with President Donald Trump (who lost the popular vote by 2.9million, remember; because of the Electoral College - theirs is an odd form of democracy) appearing to not understand the checks and balances provided by their system of three equal branches of government. He’s proving, time and again, that he’s unfit for the office.

That’s a problem with democracy: you can vote in a dictator or an ass. Then what?

All you can do then, is wait till the next election to try set it to rights, like the people of India, Australia and South Africa have this month. And then carry on believing in the worst system of government, except for all the others.