Of sporting escapes and half-forgotten heroes

The greatest serendipity for me is the stumbling across of half-forgotten heroes. For assuredly, here is the stuff of wondrous stories.

And so, late night reading, comfortably sconced in the couch by a subduing fire, I was pleased to make the acquaintance of Felice Benuzzi, Giovanni Balletto and Enzo Barsotti. Fine names, and greater characters, all!

No doubt you haven't heard of them yet; but still, theirs is a curious story of truncated heroism, humility and hubris in equal measure, and of a rise above circumstance.

The three men were Italian soldiers, captured by British forces during the Second World War campaign in Somalia, and interned at a prisoner-of-war camp in Kenya, in the shadow of the magnificent and scary 5,199m (17,058ft) Mount Kenya.

Security was pretty slack at the camp, because the prisoners had nowhere, really, to escape to. For example, the vegetable gardening duty would often let itself out by the locked gate, and sometime even lock themselves back in, when the superintendent was otherwise engaged.

Benuzzi was a mountaineer - or rather an alpinist, for this distinction is important to this story. A man who views mountains as an individual challenge, as offering a lifting of spirits, and summits the places where spiritual succor is to be gained. Alpinists, I'm told, travel lightly, for they know and feel this is right, and the better for the person and the mountain. They do not mount extravagantly overblown or cumbersome expeditions. They simply ascend as elegantly and as swiftly as possible, with the bare minimum of people and stuff.

All of which does not fit with the life of a prisoner of war. Benuzzi was compellingly drawn to Mount Kenya. He simply had to get up there. So he resolved he'd do it, then return.

He recruited Balletto, a doctor, who had done much tramping in the Alps in Europe. As for the third person in their team, Enzo Barsotti had rather odd qualifications: "...he was not an athlete nor did he seem to be in hard condition. He had never climbed a mountain in his life. The only reason we decided to try him was because he was universally thought to be mad as a hatter, and mad people were what we needed." *

The three men made preparations. They plotted their route by studying the label on Kenylon brand tinned meat, which featured a small picture of the far side of the mountain. They stole hammers from the camp workshop, to convert into ice axes. By post, they asked their families to send them warm clothes and boots from Europe. They sequestered bits of rope, used for making nets across the camp frame beds. They made crampons from bits of vehicle running boards they found in the scrap heap. They pressed the gate key into a bit of tar, and moulded their own. The sixth one worked.

They left a polite note for the camp commander, saying they'd gone for a stroll, and would be back in two weeks. They walked by night to get to the base of the mountain. That took them four days.

In the end, Benuzzi and Balletto were turned back on their one summit attempt by a fierce storm at about 4,938m (16,200 ft). (Barsotti was left further down, suffering from altitude sickness) The next day they did manage to reach the top of a subsidiary peak, Point Lenana at 4,985m (16,355ft), where they planted an Italian flag. This was possibly the very first ascent of this peak.

When they returned, they were surprisingly well received by the Camp Commandant, who in true British spirit "appreciated their sporting effort." They gave their key back. Later, they got into a bit of trouble, but not much, when the British heard about the little Italian flag flying on the mountain above their heads.

So what relevance is this story to the good people of this little island, as far away as possible from a colonial war in East Africa and the forbidding heights of Mount Kenya?

Just that the unfettered madness of Benuzzi, Balletto and Barsotti can inspire any of us, no matter where we are, or what our perceived constraints may be.

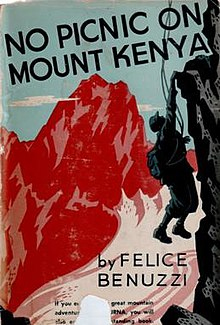

* From Benuzzi's book, No Picnic on Mount Kenya, William Kimber, London 1952. It's become something of a mountaineering classic. The book was first published in 1947 as Fuga sul Kenya - 17 giorni di liberta [Escape on Kenya - 17 days of liberty]