The art, antics and tragedy of Joy Adamson

She was a second-born daughter, and was christened Frederika Viktoria Gessner. This in a remnant part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now a part of the Czech Republic. Her stern father had wanted a boy, so he called her Fritz. She grew up in Vienna, away from her parents who had divorced, being cared for by her grandmother Oma. In an early marriage, she became Fifi von Klarwill. They were going to emigrate to Kenya, but going ahead alone on the ship, she fell for another man. Her second husband re-named her Joy, a name which stuck in the British colony they emigrated to – Joy Bally, wife of the Swiss botanist Peter Bally. Although he soon paled of his infatuation with his mercurial spouse, and arranged to get her found in flagrante with another man so they could divorce. She then married George (the co-respondent, and in on the deal with Peter) and became Joy Adamson. A name that would become world famous after the runaway success of her first book Born Free, and the film that was made of it.

The initial manuscript of Born Free was a complete mess, written in the Austrian-born Joy’s atrocious English. It had to be extensively re-written by her publisher and erstwhile lover, Billy Collins. The only lucid passages were those she lifted verbatim and without acknowledgement, from George’s field notes. Still, this did not stand in the way of her fame. But she remained a complex and unlikeable person, histrionic and with an unquiet soul. The only serenity she ever found was within her close relationship with Elsa, the lioness heroine of Born Free. She never quite connected with Pippa, a cheetah and Penny a leopard, which she later tried to rehabilitate into the wild – as she has successfully done with Elsa. Joy had three marriages, four miscarriages, a great number of unsatisfactory affairs, and was in the end murdered by an employee she had abused one time too many.

But beyond her world-wide recognition as a pioneer of big cat conservation in Africa, and her role as one of the inspirational figures of the burgeoning worldwide conservation movement, along with Jane Goodall and Jacques Cousteau et al – beyond all that, Joy Adamson is regarded as a national treasure in her adopted country Kenya for another reason. Her paintings. And this is a lesser-known thing.

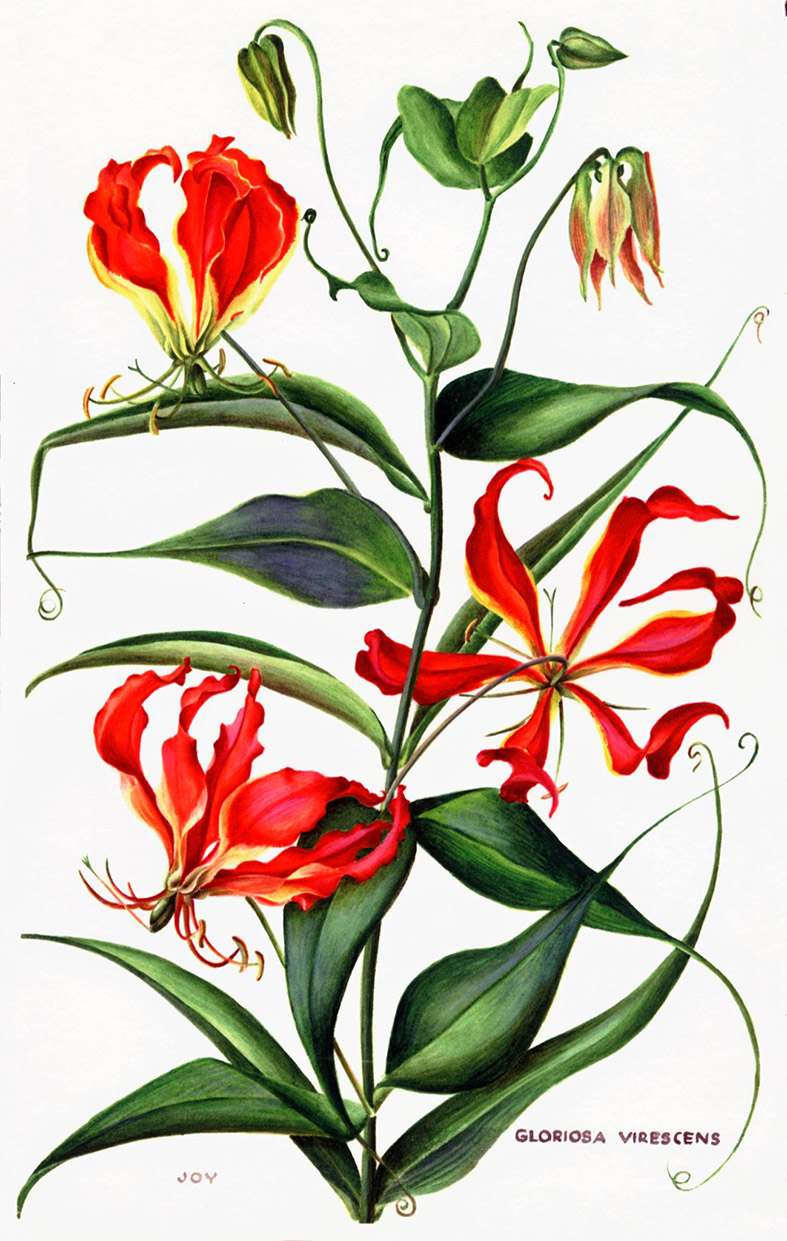

As a young woman, Frederika Viktoria had gone to art and music schools in Vienna (she was a fine piano player until she damaged her hand in a driving accident); and had dabbled in other ventures like studying fashion design – but mostly she enjoyed socialising and skiing. When she arrived in Kenya, as Fifi von Klarwill, and soon after as Joy Bally, she began doing botanical paintings. At first tutored by Peter Bally, she quickly outstripped him in output - quantity and quality. Her work, though not as precisely detailed as his, was considered more lively within the formal constraints of botanical art. Joy illustrated a number of books on Kenyan botany, most notably Gardening in East Africa.

Then, in 1945, after the weirdly messy circumstances of her abandonment of Peter Bally and her marriage to George Adamson, she became interested – nay, obsessed, that was more her nature – with the traditional costumes of tribal peoples of Kenya, and started painting them. She made great efforts to ensure her portrait sitters were authentically dressed, and that they had the approval of senior members of the tribe to go ahead. Her collection of watercolours grew, and was eventually bought by the (then colonial) government of Kenya, as they saw in it a record, more anthropological than artistic, of fast-disappearing tribal customs and dress. While the personal adornment and accessories of the people were her main interest, some of the portraits do reveal something of the individual personalities of the sitters too. Mostly Joy went out on these painting trips alone, to remote and often dangerous areas of the country. She also inveigled her way into witnessing secret ceremonies, such a circumcision for both boys and girls, as part of the project. This to be able to point the costumes that usually went with these rituals. In the end, she had produced 580 of these paintings, and they are now regarded as a priceless treasure by the post-Uhuru government of Joy’s adopted country. These paintings are most accessible through a handsome book produced in 1975, The Peoples of Kenya.

Joy also became fascinated by the tropical fish she encountered while snorkelling at the coast, and she painted these too. Although she and George lived as overtly superior and racist colonials – neither ever cooked for themselves, for instance – she remains revered in post-independence Kenya, more for her paintings than the conservation work she and George were devoted to. Joy made a great deal of money on the back of her fame which accrued through books and films of the lions, cheetahs and leopards they worked with; and she ploughed all of this money back into East African conservation causes.

Near the end of her life, Joy wrote in a prophetic passage that foresaw her violent death, that she would like to be remembered along with fellow Austrian artists-in-exile, the actress Hedy Lamar and pianist Susi Jeans. But the connection of Joy Adamson as an artist is seldom made. Her histrionic personality was also suppressed in her portrayal in the film Born Free, and in her disingenuous autobiography, The Searching Spirit. One eulogy that cuts is that of her second husband Peter Bally: “The whole world mourns Joy, except her three husbands.”

Her story then, is like that of many artists – a genius at work, driven to produce something uniquely her own; but also, something of a mess at living an ordinary life.