Among the Cinders

In New Zealand you can take off, carefree, and wander the country-side in an unhurried, unplanned fashion. You can escape your worries. You catch fish and shoot rabbits, and roast them on a bright, fragrant campfire, and filch apples and potatoes and turnips from orchards and farmers’ fields for food.

You meet beautiful, sharp, uninhibited women (if you’re an ardent young fella, like the hero). You have a harmless and funny old sage for company, and meet many more on your travels; and an arching sky of the brightest stars sings to you at night.

There are mountains and trees and funky old cars. It rains occasionally, but not much, and this doesn’t infringe too much on your grand adventure. But you do have to change plans. You’re called on to be decisive. And you come out of this wiser, and somehow more in tune with the cosmic goodness that surrounds us.

Happy ending.

It’s not exactly how the book runs, but this kinda paraphrases Maurice Shadbolt’s novel, Among the Cinders, and its enduring effect on a generation of German travelers to Aotearoa/New Zealand. And in this lies a tale of the power of myth-making, of the danger of getting lost in translation (twice), and the unfathomable, immeasurable – and sometimes unexpected – impact of art (in this case evocative fiction) on people far away.

We’re creatures of the story, I always attest, and here’s one story that has captured and transported many. Though, like real life, it has its share of let-down. Shadbolt was a great New Zealand novelist, to be sure, best known for The Lovelock Version, a rollicking family saga, and his three novels with a sardonic – nay quirky – take on the colonial conquest for these islands. These are his métier – Season of the Jew, Monday’s Warriors, and The House of Strife, can be called revisionist history, but mostly they are stylish and entertaining stories.

Someone once said that history is a story, rich and tangled and funny and weird and not always true like true is a one-sided reality, and that these novels reflect that to an excellent degree. I agree. And so, possibly, would George Fairweather, the amusing (if confused) ‘fresh-off-the-boat’ narrator of these three tales.

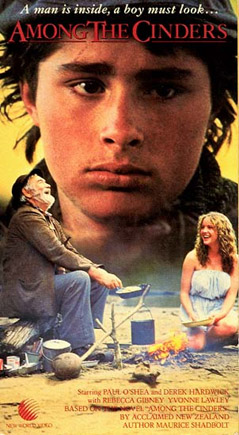

The first novel published by Maurice Shadbolt (rest his soul), Among the Cinders charts the story of young Nick Flinders, a good Kiwi lad, who’s taken away to distract him from death by his granddad Hubert. Their trip through the backblocks, and meeting Sally, is the action and essence of the story – see very loose rendering, paragraph one, above.

But here’s where it gets interesting. The book, apparently, was far more successful in its German translation. And so inspired a large audience in that country with a romantic vision of this country. Which led to the steady stream of German backpacker tourists coming to find themselves here. (You may find some this summer).

Whether they’ve actually read the book, or simply absorbed the Cinders zeitgeist from diverse sources in the collective subconscious of their country, is a moot point. And so it happened that German money, and a German director (no problem with that) came to make the feature film of Among the Cinders.

Only it never got to theatres in NZ – it’s only had one TV showing here. Reviews are a little faint. One says the movie is closer to the translation of the book, than the original version. But the old guy gets a good mention. And the poster, and Nick and Sally, look suitably stirring and romantic.

Is this a case of the story – and the myth it created – being stronger than the technicolour package of pictures? If so, there may be a lesson in that – for all of us, backpackers, directors and indigenes alike. Of countries there, islands here, and places in the mind.