The short-lived republics of South Africa

In these shut-down, isolated and possibly introspective times, you gotta have a hobby. I have been enjoying the arts of flying through space and time, and seeing the world and its history anew. I’ve also been re-visiting an arcane interest of mine – that of the truncated tales of the many short-lived republics that have come and gone in the borders of South Africa.

It’s a story with some peculiarities. All (bar one) of these half-forgotten polities were established by Afrikaans-speaking peoples, white and brown, and each was meant to become independent. None did. They were all distinctly different to the various colonies and sovereignties, whose borders were imposed on the land by the British Empire. For a start, the British colonies nominally offered the franchise to all men. The Boer-made republics were for whites only. Or blacks only, as you shall see. The British colonies were subsidised, often reluctantly but it still happened, by Britain’s coffers back home. The Boer republics were meant to go it alone, and all but one collapsed - or, like the three pathetic little surviving Volkstate (whites-only Afrikaner enclaves) recognise themselves that their continued existence is hardly viable.

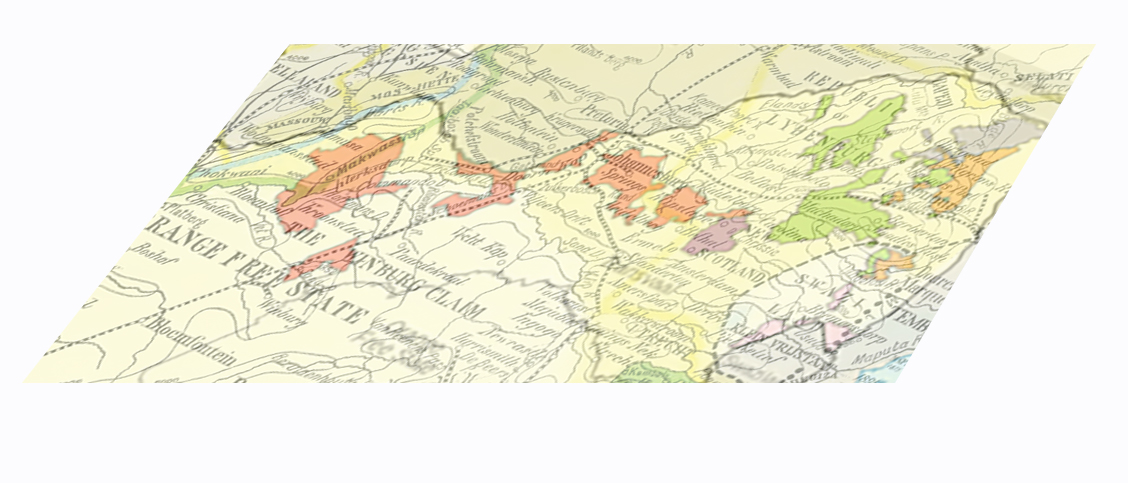

There have been no less than 54 (true!) of these short-lived Boer republics, staring with the first two, Swellendam and Graaff Rienet, proclaimed in 1795 (each lasting only a few months), and ending with those fucked-up footnotes to history that were the Bantustans, forcibly created by the Afrikaaner-led Nationalist government as the apogee of their deranged and inhumane Apartheid policy. The inhabitants of the Bantustans (and those people of the home tribe who happened to be living elsewhere, mostly in ‘locations’ attached to the main cities) would lose their citizenship of South Africa, the land of their birth. The Bantustans were supposed to become independent states. But no countries in the world community recognised them. And not one Bantustan had access to the mineral wealth of South Africa, a railway network or a seaport, or any of the other usual accoutrements of a normal country. Some were made up of un-connected pockets of land. They spread like an unsightly rash across the face of South Africa. All were far too small to sustainably house their theoretical population. The whole system of Bantustans, and their empty promise to their peoples of being ‘separate but equal’ foundered on the mighty Zulu nation’s blanket refusal, led by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, to buy the scam. Buthelezi was both chief (of his tribal clan) and chief minister (of the KwaZulu ‘homeland’). The demise of the Bantustans was immediate following the election in 1994 of the ANC government led by Nelson Mandela. They were all naturally subsumed into the new Rainbow Nation, but in practise remained as overcrowded, over-grazed places of desperate poverty, environmental collapse, and under-development.

The names of South Africa’s short-lived republics read as a litany of lunatic hopes, dashed usually by the nature of the unforgiving land. In chronological order of their demise they were: Graaff Rienet, Swellendam, Campbell, Waterboer’s Land, Daniels Kuil/Boetsap, Philippolis/Adam Kok’s Land, Natalia Republiek, Klip Rivier Republiek, Free Province of New Holland in South East Africa (Winburg), Potchefstroom, Winburg/Potchefstroom, Stokenström Kat River Settlement, Orighstad, Soutpansberg, First Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, Oranje Vrystaat, De Republiek Lydenburg in Zuid Afrika, Buffel Rivier Maatschappij (Utrecht Republic), Combined Republic of Utrecht and Lydenburg, Nieuwe Griqualand (East Griqualand), Mier Rietfontein, Grootfontein (south), Baster Gebied, Nieuwe Republiek, Diggers’ Republic, Second Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek, Het Land Goosen, Republiek Stellaland, Verenigde Staten Van Stellaland, Upingtonia/Lidjensrust, Klein Vrystaat, Griqualand West, Provisional Government of the Maritz Rebellion, Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, Ciskei, Venda, Lebowa, Gazankulu, Qwaqwa, kwaNdebele, kaNgwane and kwaZulu (not). There’s an instructive story to this last one. Add to that list the Republic of South Africa itself, declared by Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoed in 1961, which ended with the Mandela election in 1994. And, the exception to the ‘short-lived’ rule, Buysdorp.

Perhaps the saddest of these was the ‘provisional government’ of the Maritz Rebellion in 1914. When the Union of South Africa joined the First World War on the side of Britain, some senior officers of the army, led by General Manie Maritz and supported by Boer War ‘bitter einders’, rebelled and set up as allies of the Germans.

The provisional government had no land base, no logistical support, and no prospects. Its forces did however briefly, very briefly, occupy the far-removed towns of Keimoes (in the remote Northern Cape) and Heilbron (in the northern Free State). The regular South African army of 32,000 men (which included 20,000 Afrikaaners) set out to subdue the rebellion before taking on the invasion of German South West Africa.

The greatest military loss of the rebellion was provided by nature itself, when one of the rebel leaders, General Jan Kemp took his commando across the Kalahari Desert to shelter in South West Africa. He lost 300 out of 800 men, and most of their horses, all without firing a shot. It must be one of military history’s most fruitless, meaningless escapades.

The only Afrikaner polity that has lasted for since the 19ty century is the self-governing enclave of Buysdorp near the Limpopo River, founded in 1888 and still there. The inhabitants of Buysdorp are the descendants of a legendary figure of the 18th and early 19th centuries, one Coenraad de Buys. A larger-than-life figure, this rough Boer cut a swathe through the frontier regions of the Cape Colony, the Highveld and the far north, living with a succession of wives and forced concubines, who were all Khoikhoi or black African. He fathered an immense mixed-race family, a tribe of its own, the second generation of which was offered land by President Paul Kruger as reward for services rendered to the ZAR – mostly as scouts for Boer commandos. Buysdorp has endured in semi-autonomy for 130 years. This is ironic, given that Coloured people are not regarded among white Afrikaners as being of them.

There are also an additional, and equally fascinating, 16 fictional ones (District 9, Wakanda from Black Panther, The Empire in JM Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians, Azania, Bapetikosweti, The Country of the Freedom Charter etc).

From each - and from the sum of them - I believe we can learn much about the challenges of democracy, good government, the colonial enterprise, and the pitfalls of racism, authoritarianism, and societal self-delusion.

Also, we learn that republics are not necessarily democracies. What connects all the stories of the short-lived republics is the central driver of self-deceit that allowed them to try create viable societies without the participation of indigenous peoples already living in those territories. Their failures all show that racism doesn't work as a foundation to a state.

These tales also correct, to some extent, the regular European post-colonial narrative of Africa - the one where the challenges of all the post-colonial states of the late 20th Century are emphasized and dwelled-upon. Martin Meredith's book The State of Africa is one particular example. My point is that white settlers - supposedly so superior - failed so many times to create viable states; so let's give post colonial African countries a break, especially in their first experience of running governments that are expected to hold up to western ideals of democracy.

There’s some worth in this study, I think, arcane as it may seem. In the land that possibly was the cradle of mankind, these experiments in governance have some worth, given that the advance of civilisation (in my mind at least) should be marked by the acquisition and implementation of fair and sustainable ways to hold community together, and provide safety and advancement for all. So, in that way, these short-lived republics may stand as lessons on precisely what not to do. And by some kind of negative osmosis, so may we in the wider world learn the lessons of what constitutes good government, and how we can achieve it.

And that should be of use to all of us.